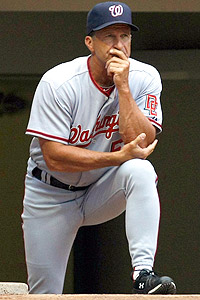

Riggleman.

Spoiler [+]

Before Thursday's chain of events, the first words that I would have used to describe Jim Riggleman -- after covering him for two seasons as manager in 1993 and 1994 and knowing him for almost two decades -- would be Organizational Man.

Getty ImagesLong considered a company man, Jim Riggleman broke with that rep Thursday.

He has been as old-school as old-school gets, always painting inside the lines prescribed by his employers, rarely straying off the team message, never publicly ripping players or tossing verbal flares like Ozzie Guillen.

Two years after I covered Riggleman, I was working at the Baltimore Sun when Davey Johnson took over as the Orioles' manager. He was brash and political through his Texas grin, taking on Cal Ripken when he wanted to move him to another position, taking on owner Peter Angelos. Sometimes I think Davey caused a stir just because he thought it was fun.

So it felt like we stepped through a looking glass on Thursday; white was black and black was white. Riggleman would have been one of the last managers I would have ever guessed would walk away from his job in midseason over a contract dispute, and yet he's headed to his Florida home. And sources say that it's the impetuous Johnson -- who probably would have been one of the most likely candidates to walk away from a team in an argument over money, as he did in the fall of 1997 -- who will get the first shot to replace Riggleman, if Johnson wants it.

Adding to the Wonderland feel of all this is the fact that the Nationals are playing the best baseball in the short Washington history of their franchise; they are a team on the rise.

Riggleman's ultimatum to Washington general manager Mike Rizzo was delivered at about 12:20 on Thursday afternoon, before the Nationals were set to play the Mariners. Riggleman had wanted his 2012 option picked up and had repeatedly asked Rizzo about that; Rizzo has repeatedly told him that it was something he would address after the season.

Perhaps Riggleman's flare-ups with Jayson Werth and Jason Marquis this season fueled the manager's concern over the impact of his lame-duck contract situation. Riggleman has always believed that it's a lot more difficult to be credible in the eyes of players if you don't have a contract for at least one year beyond the current season; I've had that conversation with him many times in the past.

But Rizzo told Riggleman he wasn't going to talk about 2012, and he wasn't going to meet about it in Chicago. That's when Riggleman told him that if it wasn't addressed, at least in a substantive conversation, then he wasn't getting on the team bus to begin Washington's road trip.

For virtually every executive in the majors, them's fighting words. For Riggleman, there was principle at stake -- he felt he deserved to have his contract option for 2012 picked up because of the performance of the team. For Rizzo, there was principle at stake -- there was no way he was going to be strong-armed in a contract situation by threat of resignation. You're saying you will resign? Then go ahead and resign.

After the game, Rizzo returned to Riggleman's office and asked him if he felt the same way; Riggleman said yes. And Rizzo replied, "Then we accept your resignation." And Rizzo immediately convened a meeting of the players and informed them of Riggleman's decision to walk away; within a few minutes, the scene in the clubhouse was surreal, with Riggleman talking to a crowd of reporters while the players prepared for their road trip.

Having known Riggleman for so long, I can write with confidence that this was a decision he had thought about -- a decision that had gnawed at him -- for weeks. He didn't wake up Thursday morning and suddenly choose that day to draw a line in the sand; this was burbling within him for a long time. He would not have quit unless he was sure it was the right thing to do.

But his choice has already hurt his reputation in a big way, with many rival executives saying privately that what he did -- walking away in midseason over a contract dispute -- is unacceptable. One high-ranked executive went so far as to say he would never hire Riggleman as a minor league manager, let alone a big league manager, because his choice showed a total lack of judgment. "I don't know if it's much different than what Manny Ramirez did," said a GM, referring to the events of 2008, when Ramirez forced his way out of Boston by basically quitting on the field.

The irony, of course, is that the Nationals' managerial job is increasingly looked at as a plum, as a position you want, because the team is loaded with talent and continues to get better. Washington is developing anchors to its rotation with Jordan Zimmermann and Stephen Strasburg; it has a young, powerful closer in Drew Storen; and its everyday lineup could include Ryan Zimmerman, Werth, Danny Espinosa, Anthony Rendon and Bryce Harper within a couple of years.

Getty ImagesLong considered a company man, Jim Riggleman broke with that rep Thursday.

He has been as old-school as old-school gets, always painting inside the lines prescribed by his employers, rarely straying off the team message, never publicly ripping players or tossing verbal flares like Ozzie Guillen.

Two years after I covered Riggleman, I was working at the Baltimore Sun when Davey Johnson took over as the Orioles' manager. He was brash and political through his Texas grin, taking on Cal Ripken when he wanted to move him to another position, taking on owner Peter Angelos. Sometimes I think Davey caused a stir just because he thought it was fun.

So it felt like we stepped through a looking glass on Thursday; white was black and black was white. Riggleman would have been one of the last managers I would have ever guessed would walk away from his job in midseason over a contract dispute, and yet he's headed to his Florida home. And sources say that it's the impetuous Johnson -- who probably would have been one of the most likely candidates to walk away from a team in an argument over money, as he did in the fall of 1997 -- who will get the first shot to replace Riggleman, if Johnson wants it.

Adding to the Wonderland feel of all this is the fact that the Nationals are playing the best baseball in the short Washington history of their franchise; they are a team on the rise.

Riggleman's ultimatum to Washington general manager Mike Rizzo was delivered at about 12:20 on Thursday afternoon, before the Nationals were set to play the Mariners. Riggleman had wanted his 2012 option picked up and had repeatedly asked Rizzo about that; Rizzo has repeatedly told him that it was something he would address after the season.

Perhaps Riggleman's flare-ups with Jayson Werth and Jason Marquis this season fueled the manager's concern over the impact of his lame-duck contract situation. Riggleman has always believed that it's a lot more difficult to be credible in the eyes of players if you don't have a contract for at least one year beyond the current season; I've had that conversation with him many times in the past.

But Rizzo told Riggleman he wasn't going to talk about 2012, and he wasn't going to meet about it in Chicago. That's when Riggleman told him that if it wasn't addressed, at least in a substantive conversation, then he wasn't getting on the team bus to begin Washington's road trip.

For virtually every executive in the majors, them's fighting words. For Riggleman, there was principle at stake -- he felt he deserved to have his contract option for 2012 picked up because of the performance of the team. For Rizzo, there was principle at stake -- there was no way he was going to be strong-armed in a contract situation by threat of resignation. You're saying you will resign? Then go ahead and resign.

After the game, Rizzo returned to Riggleman's office and asked him if he felt the same way; Riggleman said yes. And Rizzo replied, "Then we accept your resignation." And Rizzo immediately convened a meeting of the players and informed them of Riggleman's decision to walk away; within a few minutes, the scene in the clubhouse was surreal, with Riggleman talking to a crowd of reporters while the players prepared for their road trip.

Having known Riggleman for so long, I can write with confidence that this was a decision he had thought about -- a decision that had gnawed at him -- for weeks. He didn't wake up Thursday morning and suddenly choose that day to draw a line in the sand; this was burbling within him for a long time. He would not have quit unless he was sure it was the right thing to do.

But his choice has already hurt his reputation in a big way, with many rival executives saying privately that what he did -- walking away in midseason over a contract dispute -- is unacceptable. One high-ranked executive went so far as to say he would never hire Riggleman as a minor league manager, let alone a big league manager, because his choice showed a total lack of judgment. "I don't know if it's much different than what Manny Ramirez did," said a GM, referring to the events of 2008, when Ramirez forced his way out of Boston by basically quitting on the field.

The irony, of course, is that the Nationals' managerial job is increasingly looked at as a plum, as a position you want, because the team is loaded with talent and continues to get better. Washington is developing anchors to its rotation with Jordan Zimmermann and Stephen Strasburg; it has a young, powerful closer in Drew Storen; and its everyday lineup could include Ryan Zimmerman, Werth, Danny Espinosa, Anthony Rendon and Bryce Harper within a couple of years.

“

I don't know if it's much different than what Manny Ramirez did.