- 27,111

- 14,584

- Joined

- May 2, 2012

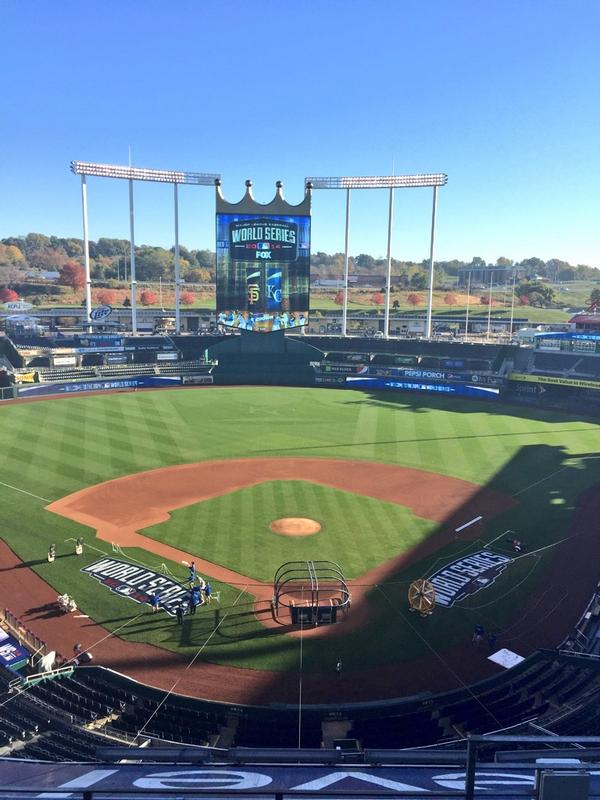

The Mets on June 28 wore uniforms that predicted the World Series did-mets-predict-the-2014-world-series … (h/t @TheSportsDude)

http://www.sbnation.com/2014/10/17/6997227/did-mets-predict-the-2014-world-series

http://www.sbnation.com/2014/10/17/6997227/did-mets-predict-the-2014-world-series

Last edited:

unless you count one start of 5+ with no runs as special.

unless you count one start of 5+ with no runs as special.