- 85,462

- 111,537

- Joined

- Sep 5, 2010

Thanks for reminding me:

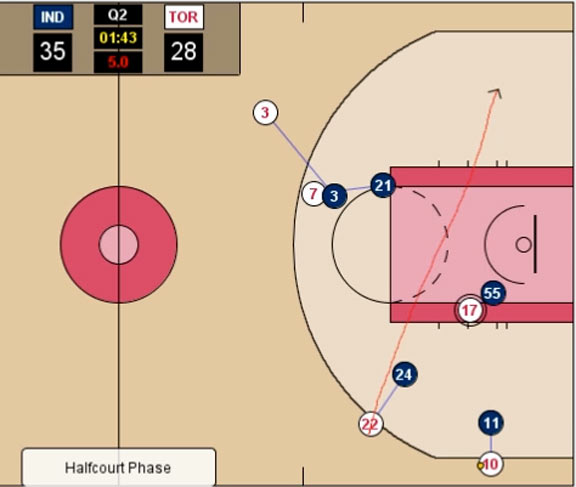

@jphanned Rudy Gay missed his last nine shots, now 9-36 (25%) in the clutch -- last 3 mins, +/- 3 pts. Keep shootin' it tho.

Those are the stats I can't put my head around.

Those are the stats I can't put my head around.