Nike Jordan

Supporter

- 32,470

- 76,721

- Joined

- Jun 27, 2002

Follow along with the video below to see how to install our site as a web app on your home screen.

Note: this_feature_currently_requires_accessing_site_using_safari

It actually does, it's a comparative analysis, which is exactly what you are mentioning. Of course it's all relative, poor in this country is poor, I'm not debating that......but when accounting for these differences on a high-level we have it better here.

"We won't gain back everything we lost," Hart said. "We sort of lost our window of opportunity in the Chinese market, at least for this growing season. Once you've established trade flow and get that shipping all worked out, it's hard to want to move away from that."

"You get what you get & you don't throw a fit"...

"You get what you get & you don't throw a fit"...The story of Vekselberg’s fall from grace in the U.S., where his American grandchildren, Yale-educated children and wife all live, is based on interviews with more than a dozen people in the billionaire’s orbit in both countries. The optimism about the future of bilateral relations that the one-time oil magnate expressed as recently as a year ago has given way to bouts of occasional public melancholy.

Through much of 2017, as the nascent Trump administration navigated controversies of its own making, Vekselberg was giving Russian officials and fellow businessmen vague yet certain assurances about his influence in the White House, according to six people who interacted with him at the time. He’d attended Trump’s swearing-in ceremony in Washington as a guest of Intrater, who’d donated $250,000 to the inaugural committee, and come back with a newfound sense of clout, they said.

Vekselberg’s spokesman in Moscow, Andrey Shtorkh,said the billionaire never tried to be a go-between on the sanctions issue. “Vekselberg has not and could not have offered anyone his help to resolve sanctions,” he said by email late Thursday. “He has no ability to do so.”

Shortly after being grilled in New York in March as part of Special Counsel Robert Mueller’s election-meddling probe, Vekselberg and the younger, brasher aluminum baron Oleg Deripaska were slapped with sanctions over Putin’s “malign activities.” Vekselberg has since lost about $3 billion of his-now $13.4 billion fortune, mainly due to declines in the market values of his minority stakes in Swiss industrial companies and Deripaska’s Rusal. And that doesn’t count the estimated $2 billion or more of stocks and cash that have been frozen or tied up in banks as a result of the U.S. penalties.

The Treasury’s decision in April to put Vekselberg in the same category as Deripaska stunned corporate Russia. That’s because Vekselberg, unlike Deripaska, has never been particularly close to Putin and sold his main Russian asset six years ago. Whereas Deripaska has been denied a U.S. visa for years over allegations of past criminal activity, which he rejects, Vekselberg has a long history of working with leading U.S. companies, institutions and politicians on commercial and charitable projects.

That’s not how some U.S. intelligence and law enforcement agencies see it. Vekselberg has been on Washington’s radar screen for years, having met the three previous U.S. presidents—Barack Obama, George W. Bush and Bill Clinton—but not Trump. In 2010, he helped organize part of then-President Dmitry Medvedev’s state visit, which included a three-day tour of Silicon Valley headlined by meetings with Apple’s Steve Jobs, Google’s Eric Schmidt and Cisco’s John Chambers.

“There aren’t many of us left, just us and our pain,” Vekselberg told a roomful of U.S. executives

“Vekselberg was deeply implicated in efforts to influence leaders and politicians here in the U.S.,” said Michael Carpenter, a former Pentagon official who oversaw Russia for the National Security Council in the Obama administration. “That’s why he wound up where he did.”

The soft-spoken 61-year-old, who’s called the sanctions against him “unfair,” has hired U.S. lawyers who recently submitted a petition to get the measures against him lifted, his spokesman said. Friends of Vekselberg say he’s genuinely shocked and saddened to be grouped on a blacklist with Syrian terrorists and Mexican drug traffickers.

Worse, they say his close and even richer friend of four decades, naturalized American Len Blavatnik, won’t take his calls at a time when Vekselberg is increasingly concerned his progeny won’t be allowed to inherit even a small portion of his fortune. Shtorkh said the men remain “friendly.”

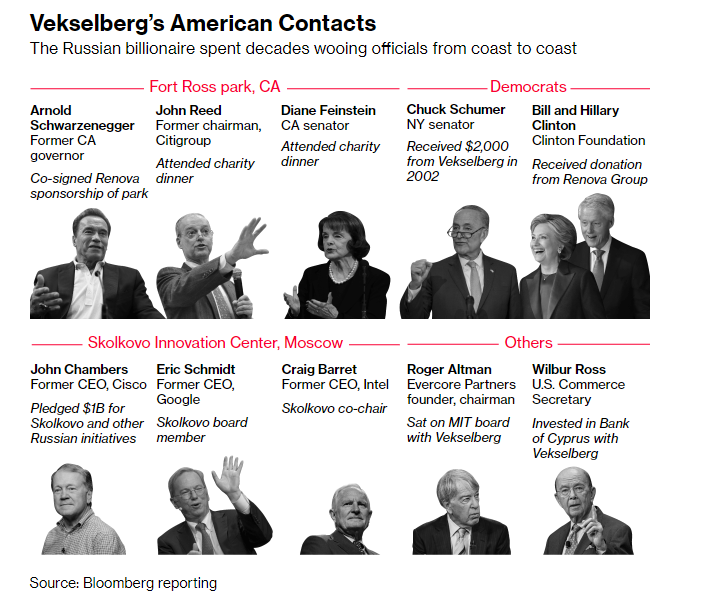

Vekselberg had spent the previous decade and a half wooing agents of influence on both U.S. coasts. He’d struck deals with Harvard and the Forbes family to repatriate iconic Orthodox bells and precious Faberge eggs. He’d saved the park that marks the first czarist beachhead in California with the backing of Republicans and Democrats alike, from then-Governor Arnold Schwarzenegger to then-Secretary of State Hillary Clinton and Senator Dianne Feinstein. He’d even won a U.S. election—to the board of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

Prior to being banned from the U.S., where he once held a green card, Vekselberg spent nearly as much time at his family’s luxury properties in Connecticut and New York as he did in Moscow. He sometimes flew into Westchester County Airport in his private jet, just like Bill and Hillary Clinton, who live nearby and had no qualms accepting a donation to their foundation of as much as $100,000 from Renova Group, his now-sanctioned holding company.

“There aren’t many of us left, just us and our pain,” Vekselberg told a roomful of U.S. executives at Putin’s annual investment showcase in St. Petersburg this May, choking up as he quoted a Soviet troubadour to describe efforts at rapprochement. His meetings with Cohen, the former Trump fixer, had just become public.

In March, during one of his last trips to the U.S., he was stopped and questioned by Mueller’s team at an airport in the New York area. They asked about his ties to Cohen, who faces sentencing on Dec. 12 for confessed crimes that include violating campaign-finance rules. Investigators also asked why he attended Trump’s inauguration and if Intrater’s $250,000 gift was actually his money.

Vekselberg “answered every question the agents asked of him” Shtorkh said. “He has nothing to hide.” Intrater, who set up the New York firm Columbus Nova in 2000 as Renova Group’s “U.S.-based affiliate,” declined to comment beyond saying that the money he gave to Trump’s inauguration was his own, not his cousin’s.

In January 2017, just after Trump assumed the presidency, Columbus Nova signed a $1 million consulting contract with Cohen, who would later become deputy finance chairman of the Republican National Committee. The firm eventually wired a total of about $500,000 to the same legal entity that Cohen used to pay hush money to an adult film star who claims to have had an affair with Trump, according to people familiar with the matter.

It isn’t clear if Cohen’s ties to Vekselberg and Intrater were discussed during the 70 hours of confidential testimony the former Trump confidante gave Mueller’s prosecutors. Cohen declined to comment on his relationships with Intrater and Vekselberg via one of his lawyers, Lanny Davis.

Intrater met Cohen by accident in a mid-town Manhattan restaurant in the fall of 2016, when a mutual friend introduced them, a person familiar with the matter said. In early January 2017, after his $250,000 gift but before Trump took office, Intrater escorted Vekselberg to Trump Tower in New York for an impromptu meeting with Cohen, according to two people with knowledge of the matter.

There, Vekselberg and Cohen discussed, among other things, a desire to improve U.S.-Russia relations, these people said. Then, sometime in March, Trump’s second full month in office, Vekselberg and Intrater met Cohen again in New York, this time to discuss a potential oil deal in the U.S. that never materialized, one of the people said, declining to be more specific.

Shtorkh said Vekselberg and Cohen met on two occasions, including one in which Cohen presented “a potential investment opportunity” that Vekselberg wasn’t interested in. “These interactions were very brief and limited, and did not in any way concern issues of the Russian-American relationship,” he said. “Mr. Vekselberg had no ongoing business or social relationship with Mr. Cohen.”

On March 14, Putin invited Vekselberg to the Kremlin for their first one-on-one meeting since 2010, according to Dmitry Peskov, the Russian president’s spokesman. The main topic of discussion was Renova Group’s infrastructure projects in Russia.

Peskov, whose communications with Cohen were at the heart of the former Trump lawyer’s admission last week that he lied to Congress, said the Kremlin was unaware of Vekselberg’s contacts with Cohen. He said Vekselberg has never offered to serve as an intermediary with the Trump administration to try to “normalize” relations.

“These issues are not the responsibility of business in general and Mr. Vekselberg in particular,” Peskov said by text message late Thursday.

In May, after Vekselberg was forced to seek about $1 billion of funding within Russia for his overseas operations, the government’s special sanctions bank charged him about 11 percent interest, far more than he was paying in Europe using the same assets as collateral, and demanded that he personally guarantee the loan, a person familiar with the matter said.

Back in the U.S., Intrater was preparing to make two more Trump-related donations. He gave $29,600 to the Republican National Committee in June 2017, and then paid $35,000 for a ticket to a Trump Victory fund dinner at the Trump Hotel near the White House.

Mueller’s interest in Intrater, who’s been questioned twice, is telling. One area his team is known to be exploring is whether wealthy Russians funneled cash into Trump’s campaign or inauguration through U.S. citizens to bypass rules barring foreign donations. Federal Elections Commission data show Intrater had never made a political donation of more than $2,600 prior to Trump.

FEC filings also show that Vekselberg himself has only given money to one American politician—Senator Chuck Schumer, Democrat of New York. That donation consisted of two payments of $1,000 each in December 2002, when Vekselberg apparently still had permanent U.S. residency.

Separating the cousins’ finances may prove difficult. Though Columbus Nova says it’s owned by U.S. citizens and Vekselberg was merely its biggest client, others say he was often the only client. A company owned by Vekselberg’s Renova Group, for example, was the biggest investor in a $300 million fund managed by Columbus Nova Technology Partners, a company Intrater set up in 2012 to invest mainly in startups, according to people familiar with the matter.

CNTP bought stakes in a raft of companies, including the digital music service Napster, previously known as Rhapsody, and the gossip site Gawker, which was driven out of business in 2016 after losing a lawsuit over a sex tape. With many of Vekselberg’s U.S. investments now frozen, CNTP’s Menlo Park headquarters has been shuttered, one of the people said.

The inroads he was making into America’s tech mecca prompted the FBI to issue a rare public warning to the entire industry

Vekselberg’s links to Silicon Valley became an issue of national security in 2014, after Ukrainian protesters chased Putin’s ally out of Kiev and Russia annexed Crimea. At the time, he’d spent four years overseeing the Skolkovo Foundation, Medvedev’s ambitious project to build a world-class tech incubator near Moscow, striking partnerships with the likes of Microsoft, Intel, Cisco and Boeing.

But by April of that year, the inroads he and Skolkovo were making into America’s tech mecca prompted the FBI to issue a rare public notice to the entire industry. Skolkovo, it warned, was a potential Trojan Horse for electronic espionage.

“The foundation may be a means for the Russian government to access our nation’s sensitive or classified research, development facilities and dual-use technologies with military and commercial applications,” the alert said. The FBI declined to elaborate on that warning.

While the FBI was urging corporate America to be suspicious of Skolkovo, Vekselberg was emerging as a white knight investor in the Bank of Cyprus—alongside Wilbur Ross, Trump’s future commerce secretary. Vekselberg is now the largest shareholder in the biggest bank on an island that’s long been a magnet for Russian wealth. Shtorkh said Vekselberg has met Ross once, in New York, “long before” he joined Trump’s cabinet.

By then, he’d catapulted to the top of Russia’s rich list with the help of Blavatnik, his longtime American partner. In late 2012, more than a year before the Ukraine conflict erupted, they agreed to sell TNK-BP, the oil company they created with BP Plc and a clutch of other investors, to state-run Rosneft for about $55 billion. The transaction, so big it needed Putin’s approval, allowed the two corporate comrades to walk away with about $7 billion in cash—each.

The pair, both born in Soviet Ukraine, met while attending university in Moscow in the 1970s, before Blavatnik emigrated to the U.S. They started jointly investing in Russian projects during the rush to acquire formerly communist assets in the 1990s, a partnership that turned out to be one of the most profitable in the annals of capitalism.

The TNK-BP windfall helped turn Blavatnik, a major donor to Trump, the Clinton Foundation and candidates from both parties, into an even bigger benefactor of American institutions. Last month, the Blavatnik Family Foundation pledged $200 million to the Harvard Medical School, a record amount for both sides. Blavatnik declined to comment on his relationship with Vekselberg through a spokesman in New York.

Since liquidating his most valuable Russian asset, Vekselberg has focused on his remaining Russian holdings, including a stake in Rusal that he co-owns with Blavatnik, as well as his overseas investments and various philanthropic endeavors. In 2014, as chairman of the Jewish Museum and Tolerance Center in Moscow, he oversaw a fundraising gala that was attended by Trump’s daughter Ivanka and her husband Jared Kushner.

Samantha Sultoon, a former sanctions specialist at the Treasury, said Vekselberg’s extensive network of contacts throughout the U.S. made him an ideal mark for policymakers seeking to send a “strong message” to the Kremlin over election interference and other actions.

“There’s a measurable outcome” when the target has U.S. assets and direct links to the U.S. financial system, said Sultoon, who’s now a visiting senior fellow at the Atlantic Council. “It makes sanctions more impactful and therefore more attractive.”

U.S. penalties are impacting Vekselberg’s investments in Europe, too, though less directly. He’s been cutting his minority stakes in Swiss industrial companies, including one, Schmolz + Bickenbach, that created a scandal of its own in Washington.

In June, two months after he was declared persona non grata in the U.S., the Chicago unit of Schmolz + Bickenbach won a $420 million contract to make bunker-busting-bomb casings for the Air Force—even though foreign companies were barred from bidding from that particular contract.

Vekselberg was unaware of the contract or even the existence of the subsidiary, according to Shtorkh. The deal was eventually terminated, but Representative Mike Kelly, a Republican from Pennsylvania, the home state of a fully American rival bidder, said he’s still seeking answers as to how U.S. taxpayers almost swelled the fortunes of a sanctioned Russian oligarch in the first place.

“It just makes no sense at all,” Kelly said.

As Vekselberg and the rest of Russia Inc. brace for Mueller’s final report, Intrater has been trying to distance himself from his deep-pocketed cousin.

Columbus Nova’s website has been scrubbed of any reference to the firm being “the U.S. investment vehicle for the Renova Group.” Its homepage now consists of a short statement saying that Columbus Nova has always been “100 percent owned by Americans” and that Vekselberg had nothing to do with hiring and paying Cohen.

But that hasn’t placated the Democrats. Four senators including Richard Blumenthal of Connecticut wrote a six-page letter to Intrater at the end of July with detailed questions about Vekselberg and Cohen, people familiar with the matter said. He’s yet to reply.

I'm not sure if this one can be beaten. Back in March, Politico reported on the WH's paper tape team.The best summary of the deplorable in chief this year.

But White House aides realized early on that they were unable to stop Trump from ripping up paper after he was done with it and throwing it in the trash or on the floor, according to people familiar with the practice. Instead, they chose to clean it up for him, in order to make sure that the president wasn’t violating the law.

Staffers had the fragments of paper collected from the Oval Office as well as the private residence and send it over to records management across the street from the White House for Lartey and his colleagues to reassemble.

“We got Scotch tape, the clear kind,” Lartey recalled in an interview. “You found pieces and taped them back together and then you gave it back to the supervisor.” The restored papers would then be sent to the National Archives to be properly filed away.

Lartey said the papers he received included newspaper clips on which Trump had scribbled notes, or circled words; invitations; and letters from constituents or lawmakers on the Hill, including Senate Minority Leader Chuck Schumer.

“I had a letter from Schumer — he tore it up,” he said. “It was the craziest thing ever. He ripped papers into tiny pieces.”

Lartey did not work alone. He said his entire department was dedicated to the task of taping paper back together in the opening months of the Trump administration.

One of his colleagues, Reginald Young Jr., who worked as a senior records management analyst, said that during over two decades of government service, he had never been asked to do such a thing.

“We had to endure this under the Trump administration,” Young said. “I’m looking at my director, and saying, ‘Are you guys serious?’ We’re making more than $60,000 a year, we need to be doing far more important things than this. It felt like the lowest form of work you can take on without having to empty the trash cans.”

The White House did not comment on the president’s paper-ripping habit. According to Young and Lartey, staffers in the records department were still designated to the task of taping together the scraps as recently as this spring.

Lartey and Young described a system that stands in stark contrast to how records management was conducted under the Obama administration, which ran a structured paperwork process.

“All of the official paper that went into [the Oval Office], came back out again, to the best of my knowledge,” said Lisa Brown, who served as President Barack Obama’s first staff secretary. “I never remember the president throwing any official paper away.”

Brown described a regimented process for dealing with presidential records. She said all paper that was going to the president “would go in a folder with labels — one color for decision memos, for example, and another one for letters. Documents would go out to the president and then come back to the staff secretary’s office in the same folder for distribution and handling. It was a really structured process.”

Brown said Obama had an eye on preserving documents for history — even ones he was not technically required to send to the National Archives. “I remember the day he sent down to me his race speech from the campaign, handwritten,” she said. “All of the campaign material didn’t need to come into the White House or go to Archives.”

Trump, in contrast, does not have those preservationist instincts. One person familiar with how Trump operates in the Oval Office said he would rip up “anything that happened to be on his desk that he was done with.” Some aides advised him to stop, but the habit proved difficult to break.

Despite the president’s apparent disregard of the Presidential Records Act, sources said, aides around him have tried to take an overly inclusive approach to what would be considered a presidential record.

Anything that’s not purely personal — even just a note handed to an aide at a rally that was passed on to Trump — has been considered a record deemed worthy of being sent to records, where staffers could make sure the White House was being compliant with the law.

That team is now smaller, after many of the career officials were cleared out earlier this year.

Lartey, 54, and Young, 48, were career government officials who worked together in records management until this spring, when both were abruptly terminated from their jobs. Both are now unemployed and still full of questions about why they were stripped of their badges with no explanation and marched off of the White House grounds by Secret Service.

Irene Porada, the head of human resources who personally terminated both men, did not respond to an email requesting comment. A White House spokesman also did not respond to a request for comment about the terminations.

Young agreed to speak to POLITICO after this reporter contacted him to inquire about his termination. He then put this reporter in touch with Lartey, whose story of his dismissal — and the work he was asked to do during his final year of work under the Trump administration — corroborated Young’s account.

Both men originally agreed to speak to POLITICO for a story about why they believe they were unfairly terminated from jobs they expected to hold onto until they retired. Both said they were forced to sign resignation letters without being given any explanation for why they were being dismissed.

In the course of explaining what their work at the White House entailed, however, both described in detail the process of taping back together scraps of paper that the president had ripped up and thrown out. Both said they were happy to discuss the oddity of a job they began to view as a sort of punishment.

They did not, however, approach a reporter with the intent to leak embarrassing information about the president.

Lartey said he was fired at the end of the work day on March 23, with no warning. His top-secret security clearance was revoked, he said. Later, five boxes of his personal belongings were mailed to his home.

“I was stunned,” he said. “I asked them, ‘Why can’t you all tell me something?’ I had gotten comfortable. I was going to retire. I would never have thought I would have gotten fired.” He signed a pre-written resignation letter that stated he was leaving to pursue other opportunities. But he is still unemployed.

Young, who was terminated April 19, said he fought back and had his official status changed from “resigned” to “terminated.”

“I was coerced to sign a resignation letter at that time,” he said. “Then they escorted me to the garage and took my parking placard.”

He described the firing as traumatic and frustratingly Kafkaesque. “The only excuse that I’ve ever gotten from them,” he said, “was that you serve at the pleasure of the president.”

I have a feeling that today is going to be interesting. This is totally how innocent people act.