- 18,115

- 11,769

- Joined

- Jan 11, 2013

The Social Credit Movement

http://www.whatswrongwiththeworld.net/2011/11/the_social_credit_movement.html

thoughts?

http://www.whatswrongwiththeworld.net/2011/11/the_social_credit_movement.html

I once said that distributism is the only economic philosophy that makes a serious attempt to conform economic theory to Catholic social doctrine. That isn't quite true. There are others, such as Catholic "corporatism", a movement that seems to emphasize both the authority of, and cooperation between, various groups in society - akin to the medieval guild system so far as I can tell.

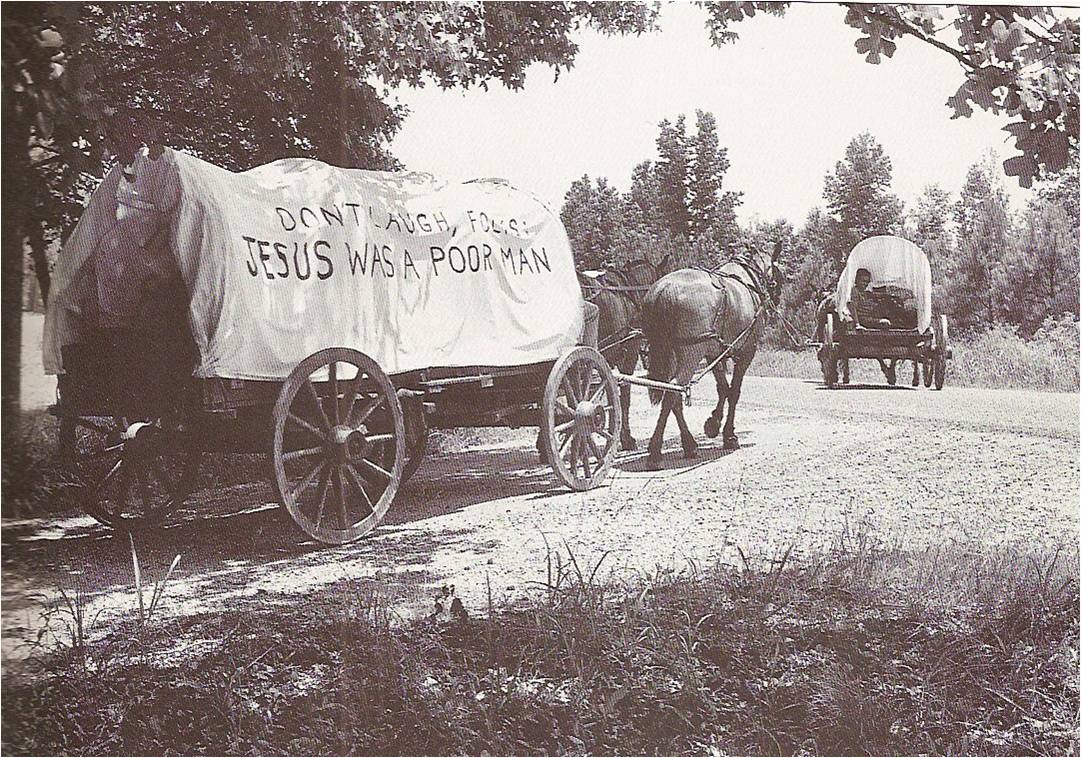

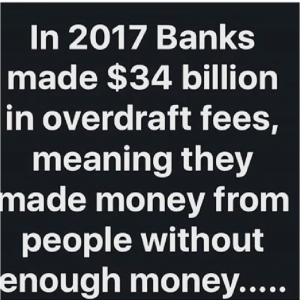

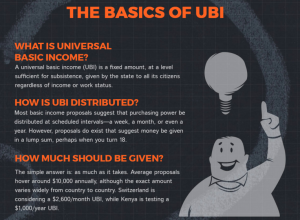

There is also the social credit movement, which I am just now learning something about. The idea here is that, as efficiency in production increases, fewer workers are required to produce the essential goods of society. The workers and entrepreneurs who would otherwise be involved in the production of essential goods are then diverted, in a capitalist economy, to wasteful and frivolous "work" for the sake of making money - money needed to buy essential goods, along with the wasteful and frivolous output of their own "work". One social credit writer noted that society would be better off paying 50% of American workers to stay home so as to minimize the damage they are doing. I can easily see this as being not too far-fetched: a great deal of work in the modern economy, including much of the best paid work, is parasitical from a social perspective.

Therefore, social credit theory proposes that it is better to pay all citizens a "social dividend" - a guaranteed income without any strings that is deemed to be a natural surplus, the rightful inheritance of everyone. Work would then be entered into with more care toward its actual value rather than its mere price in the form of wages. Under the present rule of capital, in which wages are of paramount importance, lots of valuable and important things that need doing are not done at all, or not done well. Which is the obvious consequence of too many people doing too many things that they shouldn't be doing. Presently it is the wage that allocates labor: price conquers value. And so we have become a nation of wage-earners and consumers who know the price of everything and the value of nothing.

No, I don't make posts like this just to annoy Lydia, Jeff S., and Mike T., although it's kind of fun to rattle their cages. I would remind them that Milton Friedman proposed something very similar with his negative income tax, so the concept shouldn't be anathema to the champions of capitalism. In any case, our present system is so radically broken and dysfunctional that we ought to be thinking a little beyond the ideological status quo about solutions.

There is a Catholic magazine called "Michael" that is partially devoted to the social credit movement, and you will find many relevant articles on the site. For a taste of these, you might start with "The Social Dividend to All" by Louis Even, written in the form of frequently asked questions, from which the following excerpts are taken:

Well, just go and tell a capitalist that he is getting something for nothing, when he is paid a dividend on his invested capital! On the contrary, he will call it an injustice, if he is refused his dividend.

The same is true for each member of society, who is a co-capitalist, a co-heir of a real capital, as we have just explained above — a capital which is more essential than dollars or other monetary signs which have only a representative value.

Then, a strict exchange economy cannot be a human economy, given that more than half of the population has nothing to exchange: it is the case for children, for women and girls at home, the disabled, the sick, the unemployed, the old people turned away by industry, the able-bodied men replaced by machines, etc. A strict exchange economy, an economy of “nothing for nothing” can only be a barbarous economy today. Such an economy sacrifices the individual to regulations set up for money, instead of being set up for the individual.

Treating of the distribution of goods in a socio-economic system which would set up according to the priority due to the individual, French Thomist philosopher Jacques Maritain reaches similar conclusions:

“It is an axiom for the «bourgeois» economy and the mercenary civilization that one has nothing for nothing; an axiom linked to the individualistic conception of ownership. We think that in a system where the conception of ownership outlined here above (with its social function) would be in force, this axiom could not survive. On the contrary, the law of usus communis would lead to lay down that, at least and above all for what concerns the basic, material and spiritual needs of the human being, it is right to get for nothing as many things as possible...

“For the human person to be thus served in his basic necessities is, after all, only the first condition of an economy that does not deserve to be labelled barbarous. The principles of such an economy would lead to a better grasp of the profound sense and the essentially human roots of the idea of heritage in such a way that every human, upon coming into the world, may be able to effectively enjoy, in some way, the condition of being a heir of the past generations.” (Humanisme integral, pp. 205-206)

The same is true for each member of society, who is a co-capitalist, a co-heir of a real capital, as we have just explained above — a capital which is more essential than dollars or other monetary signs which have only a representative value.

Then, a strict exchange economy cannot be a human economy, given that more than half of the population has nothing to exchange: it is the case for children, for women and girls at home, the disabled, the sick, the unemployed, the old people turned away by industry, the able-bodied men replaced by machines, etc. A strict exchange economy, an economy of “nothing for nothing” can only be a barbarous economy today. Such an economy sacrifices the individual to regulations set up for money, instead of being set up for the individual.

Treating of the distribution of goods in a socio-economic system which would set up according to the priority due to the individual, French Thomist philosopher Jacques Maritain reaches similar conclusions:

“It is an axiom for the «bourgeois» economy and the mercenary civilization that one has nothing for nothing; an axiom linked to the individualistic conception of ownership. We think that in a system where the conception of ownership outlined here above (with its social function) would be in force, this axiom could not survive. On the contrary, the law of usus communis would lead to lay down that, at least and above all for what concerns the basic, material and spiritual needs of the human being, it is right to get for nothing as many things as possible...

“For the human person to be thus served in his basic necessities is, after all, only the first condition of an economy that does not deserve to be labelled barbarous. The principles of such an economy would lead to a better grasp of the profound sense and the essentially human roots of the idea of heritage in such a way that every human, upon coming into the world, may be able to effectively enjoy, in some way, the condition of being a heir of the past generations.” (Humanisme integral, pp. 205-206)

Do not jump to conclusions which, besides, are unfounded.

First, it is wrong to say that the individual not required by production to work would get more money then he who is employed in production: both would have the same dividend, but the emp1oyee would have his wage or salary on top of the dividend.

Therefore, there would still be the same difference as before between the both of them: the amount of the wage or salary. But instead of being a difference between zero and the wage or salary, it would be the difference between the dividend, on the one hand, and the dividend plus the wage or salary, on the other hand. The stimulation of a wage or salary would therefore still be there. And in addition to this, there would be the stimulation of a dividend to all, of which the importance would increase as the social sense of the wage earners would develop.

A dividend based on the dominant part that the real community capital occupies as a modern production factor, would therefore be a generous amount.

One can understand that the transition from a diet of exhaustion to a vigorous diet requires a certain measuring out. One does not go from an unhealthy diet to a healthy diet without going through a recovery diet.

Therefore, wisdom can recommend a graduation in the amount of the periodical dividend to all.

However, from the outset, the principle must be put into application. One must come straight to the spirit of a plentiful economy and dividends to all, instead of the spirit of a rationing economy and income restricted to employment.

First, it is wrong to say that the individual not required by production to work would get more money then he who is employed in production: both would have the same dividend, but the emp1oyee would have his wage or salary on top of the dividend.

Therefore, there would still be the same difference as before between the both of them: the amount of the wage or salary. But instead of being a difference between zero and the wage or salary, it would be the difference between the dividend, on the one hand, and the dividend plus the wage or salary, on the other hand. The stimulation of a wage or salary would therefore still be there. And in addition to this, there would be the stimulation of a dividend to all, of which the importance would increase as the social sense of the wage earners would develop.

A dividend based on the dominant part that the real community capital occupies as a modern production factor, would therefore be a generous amount.

One can understand that the transition from a diet of exhaustion to a vigorous diet requires a certain measuring out. One does not go from an unhealthy diet to a healthy diet without going through a recovery diet.

Therefore, wisdom can recommend a graduation in the amount of the periodical dividend to all.

However, from the outset, the principle must be put into application. One must come straight to the spirit of a plentiful economy and dividends to all, instead of the spirit of a rationing economy and income restricted to employment.

In the way which would be considered more practical: the one requiring the least bureaucracy, the one which would necessitate the least addition to the present transfer mechanisms of the means of payment.

For example, Old Age Security pensions and the various allowances (for the blind, disabled, etc.) are paid by a cheque sent monthly to each eligible party. The same thing can be done for the monthly dividend to all.

We can also, there again, use the channel of the commercial banks, each citizen having to register with a bank in one's locality. Each month, the commercial bank would simply credit each of these accounts with the amount decreed for the monthly dividend. In this case, as in the case of the operations which we spoke about to cover the production costs by interest-free credits, the commercial bank would get from the Central Bank, upon request and without costs, the necessary amounts for the monthly dividends that it thus would have put into the accounts within its jurisdiction. And for the costs of these services, the commercial bank would be paid by the Central Bank in accordance with suitable agreements.

The monthly dividend could also very well be an accounting operation using the service of the post office. It is even the method that Douglas advocated in his scheme for Scotland: “The dividend shall be paid monthly by a draft on the Scottish Government credit, through the post office.”

With the electronic computers and other ultramodern techniques which are introduced more and more into the large accounting offices, it would not be difficult to choose a method that is fast, sure, accurate, and effective as well, for the distribution of a monthly dividend to each person. It is something all the more easy, as the collaboration of the fellow capitalist would be much more eager than that of the fellow taxpayer.

For example, Old Age Security pensions and the various allowances (for the blind, disabled, etc.) are paid by a cheque sent monthly to each eligible party. The same thing can be done for the monthly dividend to all.

We can also, there again, use the channel of the commercial banks, each citizen having to register with a bank in one's locality. Each month, the commercial bank would simply credit each of these accounts with the amount decreed for the monthly dividend. In this case, as in the case of the operations which we spoke about to cover the production costs by interest-free credits, the commercial bank would get from the Central Bank, upon request and without costs, the necessary amounts for the monthly dividends that it thus would have put into the accounts within its jurisdiction. And for the costs of these services, the commercial bank would be paid by the Central Bank in accordance with suitable agreements.

The monthly dividend could also very well be an accounting operation using the service of the post office. It is even the method that Douglas advocated in his scheme for Scotland: “The dividend shall be paid monthly by a draft on the Scottish Government credit, through the post office.”

With the electronic computers and other ultramodern techniques which are introduced more and more into the large accounting offices, it would not be difficult to choose a method that is fast, sure, accurate, and effective as well, for the distribution of a monthly dividend to each person. It is something all the more easy, as the collaboration of the fellow capitalist would be much more eager than that of the fellow taxpayer.

It would be an increase of money in the consumers' wallets, and I do not think that such a thing ever made the one who benefits by it complain. It is not when your income is raised that it hurts you. Have you ever heard one complain about a raise in one's income? It is when prices rise that everybody complains.

Cost prices would not be affected by one cent. As the social dividends are not being paid by the producers, they would not go through industry, like the wages, salaries, and dividends to the greedy capitalists; therefore, they would not go into the cost price. They would come directly from the source of the financial credit, which is a good of the people.

In the present system, which puts restrictions where none are needed, and which do not put any where some are needed, the increase of consumer money could give rise to an unwarranted increase in the retail price. But in a Social Credit system, the cost price remains in keeping with the accounting expenses during production, and the retail price is kept in check by the methods of the adjusted and compensated price, established in keeping with the first of the three principles expressed by Douglas.

In the present system, which puts restrictions where none are needed, and which do not put any where some are needed, the increase of consumer money could give rise to an unwarranted increase in the retail price. But in a Social Credit system, the cost price remains in keeping with the accounting expenses during production, and the retail price is kept in check by the methods of the adjusted and compensated price, established in keeping with the first of the three principles expressed by Douglas.

thoughts?

Last edited: