- 40

- 10

- Joined

- Jan 31, 2007

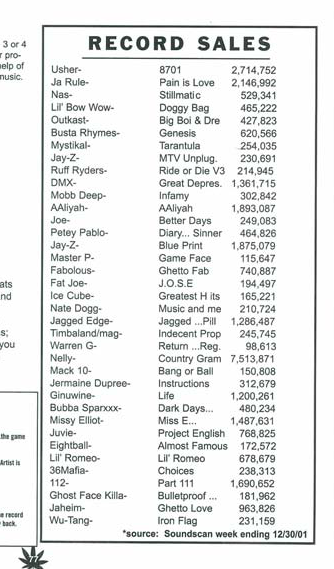

Hey NT, I was just wondering what do you feel is missing from rap/hip hop and what do you think is the cause of declining record sales? Lately i've been hearing many mainstream artists and it seems that everyone is starting to sound the same and that lyrics aren't making any sense anymore, lines are weak and rhymes don't even sound close, sometimes I hear some raps that rhymes the same word with the same word (like I just did). I mean theres people here that will say oh, he mad or a hater or you need a late pass for noticing too late, but i've noticed it for a while, but more recently it seems like theres very little effort into making words flow and changing styles from song to song. I personally think rap needs a drastic rejuvenation of something more than swagger/coke and dances.

It's good to see Drake doing his thing too, its about time that canadian artists get a chance to showcase our talents too.

It's good to see Drake doing his thing too, its about time that canadian artists get a chance to showcase our talents too.