rell826

Banned

- 6,740

- 2,125

- Joined

- Apr 25, 2013

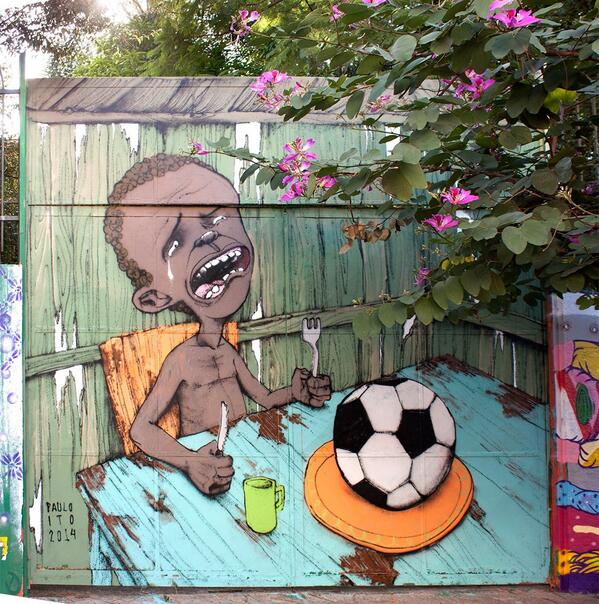

I know we have a Soccer/Futbol thread, but this topic was worthy of its own thread in my opinion given the controversy and the magnitude of not only the upcoming World Cup, but the Summer Olympics in 2016.

View media item 984507

RIO DE JANEIRO — Brazil is getting ready for a party. That's not exactly news in itself, but this time the entire world is invited. From June 12 to July 13, the country will be the stage for one of sport's most keenly watched contests, the FIFA World Cup.

But rather than celebrate the return of soccer's pre-eminent event to Brazil for the first time since 1950, much of the news has focused on the civil unrest, constant delays in construction and escalating costs that have plagued the preparations for this event.

What many people perceive as vast overspending of public money on the event led to demonstrations that made front-page news across the globe during June's Confederations Cup, which serves as FIFA's annual World Cup dress rehearsal.

The death of two workers at the Arena Corinthians stadium site in Sao Paulo, scene of the tournament's opening ceremony on June 12, also raised concerns about worker safety. In total, nine workers have died on stadium sites amid the rush to have arenas ready on time, after FIFA's deadline of December 31 proved wildly optimistic.

As we enter the final weeks before the World Cup, three of the 12 stadiums have yet to be finished.

Camila Melo of the Sao Paulo state football federation acknowledged that more protests are a possibility during the World Cup. "All organs involved in the preparation of the event are working knowing the possibility of democratic protests," she said.

However, that prospect has not dimmed Brazilians' enthusiasm for the event. "To watch a World Cup match would be something very special for Brazilians. Interest is huge, as has been proven by the enormous demand for tickets," Melo said.

When the first-come, first-served phase of ticket sales opened in mid-March, more than 200,000 were sold in the first five hours. Total ticket sales now stand at more than 2.5 million of the 3.3 million available and are exchanging on secondary markets for enormous sums. Tickets for the quarter-final, for example, were being auctioned for as much as $750—almost eight times their face value.

However, even from close up, preparations appear haphazard. The number of host cities—12 in total—has given the Brazilian Football Confederation and FIFA several projects to complete. To complicate matters even further, there have been numerous construction delays.

All of which raises the central question driving the debate about the World Cup in Brazil: Is that haphazardness part of the quirky nature of a nation seemingly constantly dressed in sun, samba and beer, or does it point to a political system that is rife with corruption?

Thanks to the global media attention that Brazil has attracted with its double sports whammy of the 2014 World Cup and 2016 Summer Olympic Games, the debate has been heard far behind its borders, spawning protests that threaten to disrupt an event most Brazilians hold dear.

According to Cynara Menezes, a well-known political observer who writes the Socialista Morena blog on the Carta Capital magazine website, Dilma Rousseff, the Brazilian president, "only speaks of political reform now, after people have been protesting on the streets."

View media item 984505

Brazil President Dilma Rousseff

FOOTBALL: MORE THAN A GAME

It is no secret that Brazil bleeds soccer. It seeps from its society's pores.

Brazil is the most successful nation in World Cup history, with five titles to its name. Despite winning consecutive World Cups in 1958 and 1962, it was their 1970 triumph that turned the world's attention to the Brazilian way of football.

Considered by many to be the greatest team in the sport's history, the side that featured the talents of Pele and Jairzinho is now the bar for which all sides since have been measured.

"It was like a rebirth," radio broadcaster and football blogger Eder Ramos de Oliveira said, explaining the redefinition of style of play that Brazil's 1970 team had on the game.

"Remember, Brazil were already two-time world champions and with some of the greatest players of the era. Nilton Santos, Bellini, Garrincha and a young Pele. But in 1970 it was perfection. It is, and always will be, the benchmark."

Since that 1970 triumph—completing a string of three World Cup titles in four attempts—there have been two more successes for the Selecao, in 1994 and 2002. And every failure is magnified when compared to a side that captivated the world more than 40 years ago.

In this part of the world, it is not enough just to win the World Cup. Brazil must win with panache. The notion of o jogo bonito, football as an art form, is paramount.

The World Cup unites Brazil like no other event, perhaps aside from Carnival. Whilst there are big screens erected to watch in public, the majority watch the games at home surrounded by family and friends.

Then, should the side be successful, the people take to the streets in a cacophony of color, celebration and ecstasy. This year, every day of a Brazil game will be a national holiday.

View media item 984504

Pele rides on the shoulders of teammates after 4-1 win over Italy in 1970 World Cup final.

POLITICAL PROTESTS BECOME THE STORY

Despite Brazil's success at the Confederations Cup—they lifted the trophy after beating Spain 3-0 in the final—the biggest story was the protests that swept the nation in an enormous wave of anger and rebellion.

What started as a minor protest in Sao Paulo against a 10-cent rise in bus fares came to embody every grievance the people could muster against the government.

Thanks to social media, especially Facebook and Twitter, action reached all cities associated with the Confederations Cup. In Rio de Janeiro, a union between the middle and working classes—unprecedented previously—left a trail of destruction in protests which came to represent a stand against huge public spending on the World Cup, a figure that has reached $13 billion, with the majority of that money coming from public funding, as acknowledged by the Brazilian Ministry for Sport.

By comparison, the last World Cup, held in South Africa, cost a little more than $1 billion to prepare.

So charged is the atmosphere that a middle-class protester only wanted to give us his first name, Diego. He is a 23-year-old university student with hopes of one day becoming an international diplomat and is naturally concerned that too much exposure could hamper his future path and prospects.

"The reasons we acted were simple. What was a source of pride became a source of embarrassment," he said of hosting the World Cup. "But it went beyond that. Our actions came to be a symbol for everything we feel is wrong with the country. The fact such small objections went nationwide so quickly is proof we are not the only ones who feel anger and resentment."

Those sentiments are easy to understand. Billions of dollars are being poured into what is essentially a month-long celebration, and the public is being forced to foot the bill.

The protests go beyond huge public spending. They are against the wasteful use of public money.

It is worth noting that when Brazil was awarded the World Cup in 2007, the estimated cost of stadium construction was $924 million. But a problem that always existed with the building of so many new stadiums was the possibility that many of them would be of no further use after the World Cup.

In cities such as Cuiaba, Natal and Manaus, which have a lack of football heritage, that danger is acute. But no city faces heavier criticism in that regard than the capital Brasilia, whose stadium construction costs could top $900 million, more than three times its initial budget.

As Menezes, one of the foremost writers on Brazilian politics today, explained, while the protests began over a small rise in bus fare in Sao Paulo, "they spread to involve many current problems in Brazilian society."

View media item 984502

Protesters march toward the stadium where a Confederations Cup semifinal was taking place.

Citizens snatched their chance whilst the world was watching. Protesters saw a chance to make their voice heard, not only in their homeland but around the globe, and they took it.

But were they successful? Well, bus fares were lowered to the original fare. And people came away from the Confederations Cup speaking not about Brazil's increased chances of a repeat performance during the FIFA World Cup, but of the political movement that seemed to be sweeping the length of the land and threatened to stay.

Subsequently, in order to protect themselves from further incidents during the main event, the federal government is now trying to push through a law banning public protest.

Photographer Carlos Alberto da Silva Junior has been working in Rio de Janeiro for 19 years and recently covered the protests at the city's Central train station, where a cameraman was fatally wounded during a battle between protesters and police.

He believes protests will occur irrelevant of any laws passed. "During the World Cup, it is going to be a war," he said.

At the start of 2014, the Brazilian federal government drafted in 10,657 National Force operatives to help police deal with ongoing protests that may reach a crescendo during the World Cup. All have received specialist training in dealing with civil unrest.

WHAT'S TRIGGERING THE PROTESTS?

It is impossible to discuss the World Cup without mentioning Brazilian politics. It is involved in every aspect of life.

How can a government, fully aware of the poor standard of schools and hospitals in the public sector, justify spending a figure that is expected to reach $13 billion on a month-long sporting event?

"It should have been possible to use money from private investment for the World Cup, whilst public money is invested in health and education," Menezes said. "It is a question of priorities.

"For me, the biggest problem with the World Cup is the huge overspending on stadiums. The World Cup will place Brazil in the middle of the planet's attention, for good and for bad. Maybe it won't be such a bad thing to highlight our problems, our inequalities, our poverty. I sincerely prefer that to hiding them from view."

Andrea Cordeiro, from the Ministry for Sport, counters that such criticism is unjustified.

"There is no foundation in that whatsoever. Brazil is not failing to spend on health and education to fund the World Cup. On the contrary, investment in health and education has tripled since 2007. Since 2010, Brazil has invested $358.8 billion in health and education."

What is also ignored by such criticism, Cordeiro said, is the long-term benefit such investments will have for Brazil. "The spending is investment in airports, ports, security equipment and technology. They are investments in Brazilian cities which the inhabitants will benefit from beyond the World Cup."

After making front-page news across the globe, protests at the World Cup could still take on a huge mantle, but not everyone agrees that will be the case, political writer Rafael Cal said.

"There is a widespread expectation that people will take to the streets in greater numbers than last year," he said. "But I don't think the middle-class protesters, who were heavily involved during the Confederations Cup, will be as vociferous this time around."

View media item 984500

A protester in Rio de Janeiro is doused with tear gas by a member of the Brazilian police.

However, with less than a month to go until the World Cup, Black Blocs and other anti-government movements are already making plans for action.

"So we ask: Who is this Cup for?" socialist Keila Lucia de Carvalho said. "It has become evident it is not for the majority of the Brazilian population."

The protests, missed construction deadlines and overspending have caused some Brazilians, including Pele, to become disenchanted with Brazil's decision to host the World Cup, an event that was meant to be a dramatic expression of Brazilian culture, a demonstration that there is more to this country than sporting prowess and rife political corruption.

Roberto Goulart Souza Ribeiro, 38, is one of them.

"When Brazil were awarded the World Cup [in 2007], it was a proud moment," said Ribeiro, who is from the host city of Belo Horizonte. "Brazil was in a good moment economically. There were many plans for development of infrastructure and airports.

"Now, in 2014, what have we seen? There have been very few improvements to infrastructure. Building works at Galeao [Rio de Janeiro's international airport] are not concluded. The budget for every stadium is over the limit.

"Hosting the World Cup has left me with feelings of frustration. There have been no benefits for the Brazilian people."

To ensure that the World Cup party is one to remember for all, there are numerous obstacles to overcome. Besides limiting the violence during protests, construction must be hurried to be finished on time.

All building work was supposed to be finished by December 31, 2013, the FIFA-imposed deadline. But on May 16, 27 days prior to the tournament, work to the external structure of the Arena Corinthians in Sao Paulo was still being carried out.

View media item 984497

The Pantanal in Cuiaba arena under construction.

Structural work to the temporary stands is still not finished despite numerous warnings from FIFA. Two other arenas, the Pantanal in Cuiaba and the Baixada in Curitiba, are undergoing test events to prove their safety.

THE COUNTRY OF TOMORROW, TODAY

The World Cup preparations, over the last seven years, have been like a telenovela—one of the famous Brazilian television soap operas. The Brazilians have a famous saying: "Sempre se da um jeito."

There's always a way. In the nick of time, everything will sort itself out.

During this wild ride, there has been happiness, pride and optimism. There has also been anger, shame, violence and even death in the rush to get everything ready to receive the world.

The World Cup dominates Brazil, and not only because 2014 is the year the five-time champions host the competition. As a source of national identity, Brazil's glorious footballing past has been an enormous point of pride for its people.

But the buildup to this edition has evoked emotions and actions of a completely different sort.

The World Cup is facing major threats, not to mention the real possibility of a wasted opportunity.

It seems that Brazil has been "the country of tomorrow" for decades. There comes a point when that must be transformed into progress.

This was supposed to be that time.

Robbie Blakeley graduated from the London School of Journalism before moving to Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, in May 2010. He has worked as a sports reporter for The Rio Times for four years and has contributed to When Saturday Comes, Xinhua and The Daisy Cutter. He has also been featured on several radio broadcasts, including BBC 5 Live and TalkSPORT.