It all makes the Orioles look bad, which isn’t fair. It was supposed to be easy enough for the Orioles to sign both Yovani Gallardo and Dexter Fowler. Then, within a few days, the Gallardo talks nearly fell apart, and the Fowler talks did fall apart. Instead of the Orioles and Fowler having an agreement, it turns out Fowler wanted a one-year opt-out, which the Orioles wouldn’t give him. That’s a perfectly defensible stance, but here’s where we are now: Baltimore doesn’t have Dexter Fowler. Fowler has gone back to the Cubs, for a year and $13 million. It’s all been a pretty stunning turn of events, and the breakdown in the Baltimore talks has allowed the Cubs to answer the last big question they had.

For the Orioles, it’s a bad look, and it’s frustrating, because now they have to keep poking around to fill a hole they thought they’d fill. It’s probably somewhat bad for morale, and now you can likely expect the Orioles to get in contact with the Reds about Jay Bruce. It’s not the worst fallback in the world. Yet this is all really about the Cubs. The Cubs get to keep Fowler, if only for a year. It reduces the uncertainty for what’s pretty clearly a World Series favorite.

The Cubs actually made two moves, that are obviously linked. They signed Fowler, and while the deal comes with a mutual option for 2017, those are almost literally never picked up. And the Cubs also sent Chris Coghlan to the A’s, in exchange for Aaron Brooks. The Coghlan/Brooks move is interesting enough on its own, but we can just fold it in here. Coghlan wasn’t going to have a place in Chicago with Fowler back in the fold. Brooks could prove to be useful, this year and in several future years.

From the Oakland perspective, quickly, adding a year of Coghlan is about adding versatility. He’s a pretty decent hitter, at least against righties, and he’s capable of playing both the infield and the outfield, so he’s one of those guys you get to think of as a worse version of Ben Zobrist. The A’s roster picture looks to be complex, but there are serious questions about Coco Crisp, and about Billy Butler, and Eric Sogard hasn’t hit. Adding Coghlan sweeps more playing time to reliably adequate players, allowing the A’s to lift the floor. Brooks wasn’t and isn’t nothing, since the A’s don’t feature a ton of pitching depth, but Brooks was definitely on the outside of the rotation picture looking in. So they opted to make the exchange, in an effort to build a better 2016.

There are things for the Cubs to like about Brooks. There were things for the Cubs to like about Coghlan, but he was superfluous. Brooks has racked up barely any service time. He can be optioned to the minors, and in the minors he’s been a successful strike-thrower. There’s still work for Brooks to do if he wants to cement himself as a big-leaguer, but he owns a good changeup, and he’s maybe a tweak away from being Kyle Gibson, who owns an almost identical repertoire. Gibson himself is maybe a tweak away from being a No. 2, but Gibson now is a decent comp for Brooks, if he can locate a little bit better. Brooks slightly improves the Cubs’ future pitching situation, and he’s also more depth for the year ahead.

Let’s talk about that year ahead. And let’s talk about the bigger move, and its implications. The Cubs, as you well know, project to be perhaps the best team in baseball. It’s been that way for a while, and adding Jason Heyward provided a massive boost. Ever since the Cubs lost Fowler and added Heyward, there’s been speculation they could add a center fielder. Failing that, Heyward would move over to the middle, and the Cubs would trust in his adjustment. He’s still young, and he’s still plenty good.

As of this morning, Heyward looked to be the starter in center. And when we’ve talked about any potential Cubs weaknesses, people have looked to center field. Just based on positional adjustments and what Heyward has done in right, it objectively makes sense that Heyward could and would be fine in the middle, but then, you never really know how a move is going to go until it goes. Heyward hasn’t played that much center field. Maybe he’s unusually cut out for right. Maybe center would give him some fits; maybe it would have an effect on his hitting. Heyward’s always been a complicated player. Basically, there was some uncertainty around the Cubs making a huge splash and then asking that investment to try something new.

Now that’s history. Now it’s going to be Fowler in center, mostly, and Heyward back in right, mostly. Fowler isn’t considered to be a plus defensive center fielder, but he’s at least a proven center fielder, just as Heyward is a proven right fielder. The Cubs know what they’ll have in Fowler, and now they should have a better idea of what they’ll have in Heyward, since he gets to stay in his comfortable position. I have to say, I think Heyward could’ve managed center just fine, but this should improve the odds that Jason Heyward performs like Jason Heyward. There are fewer adjustments for him to make, this way, creating a clearer path to 5 WAR.

So that big question about Heyward is no longer relevant. The Cubs don’t have a great glove in the middle now or anything, but they’re damn sure they’ll have a great glove in right. The overall defensive picture is improved, because Heyward should be Heyward, and now Kyle Schwarber and Jorge Soler will split time in left. They’re both going to play a little less than they might’ve been expected to a few days ago. But they will play, and if anything this gives the Cubs further protection since Schwarber is a small question mark, and Soler is a bigger question mark. They’ll be asked to do less, but they’ll still be around and hopefully developing.

For Soler, this is like an organizational compromise. He’s not going to be an everyday player, but he also hasn’t been traded. So for now the Cubs get to hang on to his promise and then later on they can re-visit his place in the system. If he gains value, he could be flipped for a longer-term center fielder. If he doesn’t gain value, well, that’s what happens, but at least he’s not a starter. It would’ve been difficult for the Cubs to willingly shed his potential, so this isn’t a bad path.

The Cubs get to keep Soler. They improved their starting-pitching depth. And most importantly, with Fowler coming back, the Cubs get to return Heyward to where Heyward can be Heyward. There’s less uncertainty on this roster than there was on the same roster a day ago, and for a team in the Cubs’ favored position, uncertainty is the enemy. Uncertainty is what threatens to drop the Cubs back to the pack. Certainty keeps the Cubs a step or two ahead. It’s not like the Cubs have figured out how to make baseball predictable or anything, but they’ve taken a step to make it less unpredictable, and the predictions we have see the Cubs as the best team in the league. You can understand why they want to lock that in.

Navigation

Install the app

How to install the app on iOS

Follow along with the video below to see how to install our site as a web app on your home screen.

Note: this_feature_currently_requires_accessing_site_using_safari

More options

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

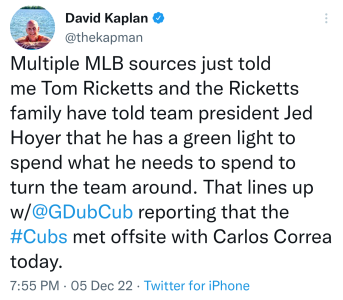

Official 2023 Chicago Cubs Season Thread Vol: (17-17)

- Thread in 'Sports & Training' Thread starter Started by CP1708,

- Start date

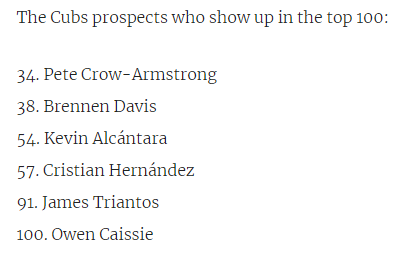

While the Cubs were rebounding from a last-place division finish in 2014 to the National League Championship Series last year, they added four rookies with All-Star potential to their lineup in Kris Bryant, Addison Russell, Kyle Schwarber and Jorge Soler. That group was just the first wave of what might prove to the finest collection of position prospects in years.

Chicago has more quality hitters on the way, if not enough spots in the lineup to accommodate them all. Catcher Willson Contreras will be pushing for big league time by the end of this season. Former first-round Draft picks Albert Almora and Billy McKinney will be trying to squeeze into a crowded outfield in the near future. Shortstop Gleyber Torres, second baseman Ian Happ and third baseman Jeimer Candelario soon will add to an infield logjam.

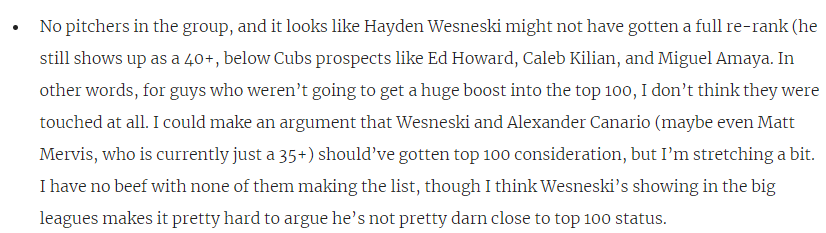

Cubs pitching prospects don't get nearly as much hype and probably won't make a significant impact at the big league level in 2016, but there are some intriguing arms in the system. Duane Underwood can flash three plus pitches, while Dylan Cease and Oscar De La Cruz opened eyes last summer and will make their much-anticipated full-season debut in April. Chicago has invested heavily in high school pitching in the last two Drafts, hauling in Cease, Bryan Hudson, Justin Steele and Carson Sands.

Biggest jump/fall

Here are the players whose ranks changed the most from the 2015 preseason list to the 2016 preseason list.

Jump: Willson Contreras, C (2015: NR | 2016: 2)

Fall: Jen-Ho Tseng, RHP (2015: 11 | 2016: 24)

Best tools

Players are graded on a 20-80 scouting scale for future tools -- 20-30 is well below average, 40 is below average, 50 is average, 60 is above average and 70-80 is well above average.

Hit: Billy McKinney (60)

Power: Eloy Jimenez (60)

Run: D.J. Wilson (65)

Arm: Gleyber Torres (60)

Defense: Albert Almora (65)

Fastball: Dylan Cease (70)

Curveball: Bryan Hudson (60)

Slider: Jake Stinnett (55)

Changeup: Duane Underwood (55)

Control: Ryan Williams (60)

How they were built

Draft: 18

International: 7

Trade: 5

Breakdown by ETA

2016: 5

2017: 9

2018: 13

2019: 3

Breakdown by position

C: 2

1B: 1

2B: 1

3B: 2

SS: 1

OF: 8

RHP: 12

LHP: 3

1. Gleyber Torres, SS

2. Willson Contreras, C

3. Ian Happ, 2B/OF

4. Duane Underwood, RHP

5. Albert Almora, OF

6. Billy McKinney, OF

7. Jeimer Candelario, 3B

8. Dylan Cease, RHP

9. Oscar De La Cruz, RHP

10. Eloy Jimenez, OF

11. Pierce Johnson, RHP

12. Donnie Dewees, OF

13. Bryan Hudson, LHP

14. D.J. Wilson, OF

15. Eddy Julio Martinez, OF

16. Carl Edwards, Jr., RHP

17. Justin Steele, LHP

18. Mark Zagunis, OF

19. Ryan Williams, RHP

20. Dan Vogelbach, 1B

21. Trevor Clifton, RHP

22. Jake Stinnett, RHP

23. Carson Sands, LHP

24. Jen-Ho Tseng, RHP

25. Victor Caratini, C

26. Christian Villanueva, 3B/1B

27. Corey Black, RHP

28. Jacob Hannemann, OF

29. Brad Markey, RHP

30. Josh Conway, RHP

2017-18 ETA's.

- 1,888

- 504

- Joined

- Sep 7, 2011

Cubs sign Shane Victorino to a minor league deal. good competition

MESA, Ariz. -- Some people have epiphanies when they're struck by bolts of lightning. Addison Russell inadvertently glimpsed his destiny via a beer sign on the north side of Chicago.

In 2010, Russell was a 16-year-old high school sophomore playing in the Under Armour All-America Baseball Game at Wrigley Field when he noticed a neighborhood billboard with a picture of a frosty cold brew beside the words "Where Clark Met Addison." As a product of the Florida panhandle, Russell was unfamiliar with the intersection at which Wrigley sits. But the sign resonated with him anew when the Chicago Cubs acquired him from the Oakland Athletics by trade in July 2014.

"At the time, I was like, 'What does that sign mean?'" Russell said. "Of course, it was the corner of Clark and Addison Streets. I thought that was pretty cool. When I got traded to the Cubs, that thought came back into my head: 'Maybe I have a chance to play in that stadium again.'"

For all the Cubs' torment, they stack up nicely with their MLB competitors in the shortstop department. Ernie Banks won two most valuable player awards at short and hit 277 of his 512 home runs at the position on his journey to Cooperstown. Don Kessinger could really pick it back in the day, and Shawon Dunston possessed the mother of all howitzers. Those three are joined by Joe Tinker, the only .262 hitter to be feted with a Hall of Fame plaque and a poem for the ages.

Against that illustrious backdrop, the argument can be made that Russell arrives at the biggest crossroads and the most exciting time in franchise history. With the team's world championship drought at 108 years and counting, the Cubs are coming off a 97-win season and generating buzz that has prompted the fan base to think the previously unthinkable. Wrigley Field, like the 25-man roster, is undergoing major renovations, and Russell arrives on the scene alongside Carlos Correa, Xander Bogaerts, Francisco Lindor and Corey Seager in a budding "golden age" for shortstops.

If the Cubs are the least bit anxious about entrusting the pivotal defensive position on the field to a kid who is four years removed from anchoring the Pace High School Patriots' starting infield, Russell eases their concerns by arriving at the ballpark early, putting his head down and getting down to business every day. He's a perfectionist and a stickler for detail who should come with a "no maintenance required" label.

"He's got a good head on his shoulders," Cubs president of baseball operations Theo Epstein said. "He's our youngest player, but he might be the one we worry about the least."

During the Cubs' first full-squad workout Wednesday at Sloan Stadium, Russell took his hacks in a batting practice group with Jason Heyward, Jorge Soler and his new double-play partner, Ben Zobrist. In idle moments outside the cage, Russell flipped his bat back and forth between his legs and from one hand to another with the dexterity of a baton twirler.

As Russell worked, the team's new community ambassador looked on approvingly from behind a pair of shades and a Cubs spring training cap. Hall of Fame second baseman Ryne Sandberg knows the real deal when he sees it. Russell has already gained Sandberg's seal of approval.

"His potential is very good," Sandberg said. "He reminds me of a young Barry Larkin, maybe. He has that kind of look and feel. He's very athletic, and he can improvise on making throws when he gets to balls. There's a little bit of an acrobat in there. But there's some steadiness with him too, which is what you want at the position."

Oakland executive Billy Beane has also invoked the Larkin comparison, while Cubs manager Joe Maddon flashed back to a certain 14-time All-Star the first time he watched Russell field grounders with technical precision.

"He's one of the more efficient young infielders I've ever seen, when it comes to his movements," Maddon said. "I can only compare him to Derek Jeter. For me, Jeter had the perfect method of picking up a ground ball -- like a Gary DiSarcina. It was very simple, very boring. I think Addison fits in that category."

Mature beyond his years

It would be an understatement to say Russell handled his rookie year with aplomb. Although his 149 strikeouts and .242/.307/.389 slash line were signs that some growth is in order at the plate, Russell displayed considerable pop with 29 doubles and 13 homers in 475 at-bats. That's the same number of homers new Cubs outfielder Jason Heyward produced in 547 at-bats.

"This guy is going to hit," Maddon said of Russell. "If you shake his hand, he has huge paws. Watch him in BP, and it's loud, and it's far."

Russell's glove is his calling card at the moment. He ranked fourth among second basemen with a Defensive Runs Saved of plus-9 the past season, according to Baseball Info Solutions, and he tied for fourth among shortstops with a DRS of plus-10. He possesses a double-barreled ability to make Web Gems and turn routine ground balls into foregone conclusions.

Russell honed his fundamentals under the tutelage of Karl Jernigan, a former Florida State outfielder who played in the San Francisco Giants' chain in 2002-03. He learned to field balls in front of his body, and he embraced the idea that everything begins with efficient footwork and a solid base. Punctual to a fault, Russell prefers to beat the ball to a spot, rather than rely on athleticism or pizzazz.

Nitpickers point to his low throwing slot and an arm that wore down as the 2015 season progressed. But Russell has exceptional accuracy and hits the first baseman in the chest every time.

Russell's slow heart rate was a gift from a higher power. During the 2014 Cubs Convention, he surprised attendees by revealing that he didn't watch much baseball as a youth, and his boyhood idol was the late martial arts icon and action film star Bruce Lee. For a player with so much baseball rat in him, Russell grew up with an appreciation for multiple sports. He played football until his sophomore year in high school and warmed to the contact as a running back.

"I could barrel through the line," he said. "I lowered my shoulder. I wasn't scared of getting hit, and I had some good footwork and juking moves. It's all about reading people's eyes. Whenever you come head-to-head downfield with the safety, it's a pretty cool feeling. You do the best you can so he can't tackle you. That's kind of a game I played. I imagined myself as I'm trying to run away and these guys are trying to catch me."

After the Athletics chose Russell with the 11th pick in the 2012 draft and, with a $2.625 million signing bonus, dissuaded him from accepting a scholarship to Auburn University, Russell headed to the Arizona Rookie League and began a quick ascent through the minors. He also paid off a personal debt to the people who so faithfully supported him in his pursuit of a dream.

Russell is the oldest of four children, and the family spent lots of time moving around during his youth. In an effort to inject some stability into the dynamic, he spent a chunk of his bonus on a two-story home with an acre of land for his parents and three siblings in his native Pace, Florida.

Russell feels a special sense of gratitude to his mother, Milany, and his step-father, who entered his life when he was a toddler. Wayne Russell, who works as a cook at the Tuscan Oven pizzeria in Pensacola, was always available with tough love or an encouraging word.

"He always believed in me," Russell said. "The little stuff he used to get on me about hasn't changed. He sees the little kid in me, and it's really cool."

A second chance

His outward calm notwithstanding, Russell is not above using stray personal slights for motivation. He was a bit heavy and out of shape coming out of high school, and some members of the scouting community and the media speculated that he lacked the attributes to play shortstop in the pros.

After the Cubs chose outfielder Albert Almora at No. 6 in the 2012 draft -- five spots ahead of Russell -- team officials got an update when they saw Russell play shortstop in the Arizona Fall League in 2013. They quickly realized they might have passed on something special.

"I wouldn't say we whiffed, but we didn't spend the time we needed to on him," said Jason McLeod, the Cubs' senior vice president of player development and amateur scouting. "I saw the physicality and the bat speed and the way he carried himself in the Fall League, and I was like, 'Oh, boy.' As the guy who oversees the draft, I was kicking myself a little bit."

McLeod was understandably thrilled when a fortuitous set of circumstances brought Russell to the corner of Clark and Addison eight months later. In July 2014, the A's were 53-33 and pushing to get over the postseason hump when vice president of baseball operations Billy Beane acquired starters Jeff Samardzija and Jason Hammel from the Cubs for a package that included Russell and outfielder Billy McKinney. Although the trade looks bad for Oakland in hindsight, Epstein passes on taking a victory lap.

"Billy is one of the few general managers who's not afraid to make a deal like that to increase his chances of winning in the postseason," Epstein said. "It was a brave trade, and I admire him for making it. We were just in a different place than they were. I like to think if we were in the same place, I would have had the guts to acquire what our big league team needed, which is what he did."

Although everything is trending positively for Russell, he approaches the 2016 opener in unfinished-business mode. After helping the Cubs reach the playoffs, he suffered a hamstring injury in the division series against the St. Louis Cardinals and was a spectator when Chicago dropped four straight to the New York Mets in the NLCS.

At the Cubs Convention in January, Russell spent some time getting acquainted with Zobrist, who signed with the team as a free agent in December. Russell made a positive first impression when he brushed aside talk about middle infield dynamics and told Zobrist, "I don't care about anything else. I just want to win." Russell also made it clear he was itching to arrive in Arizona to start spring training.

"You can see the anticipation," Zobrist said. "Probably more than anybody else in here, he wants to be out on the field right now. He's just like a horse who's bucking right now, and you need to let him out of the pen."

Seemingly, a new wonder awaits each day. In August, Russell's fianceé, Melisa Reidy, gave birth to a baby boy named Aiden Kai, and in January, he and Melisa were married. Russell always felt a sense of responsibility as the oldest of four children, but the flurry of recent life events has taken his dedication to a new level.

As his hero, Bruce Lee, once observed, "If you are in a hurry, you will never get there."

With purpose in his step and resolve in his eyes, Addison Russell is methodically following life's plan. It doesn't take a billboard to confirm he has landed in the right place.

- 37,287

- 19,666

- Joined

- Nov 17, 2004

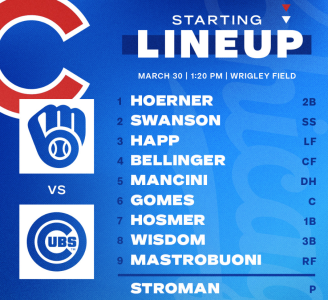

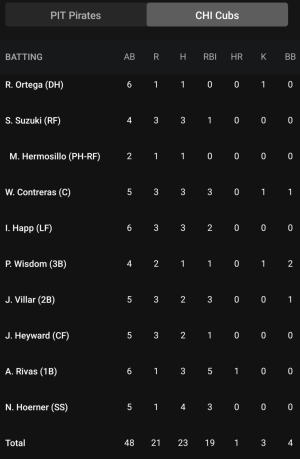

GOAT lineup.

- 1,292

- 53

- Joined

- Dec 31, 2003

Single game tickets went on sale today. Bought tickets to 3 games already. Hopefully I can go to a bunch more if prices don't get outrageous.

- 2,660

- 738

- Joined

- Jan 13, 2004

This lineup is so disgusting.

Welcome back Dex!

Soler/Schwarbs/Baez platoon

Welcome back Dex!

Soler/Schwarbs/Baez platoon

MESA, Ariz. -- Since the unexpected return of Dexter Fowler to the Chicago Cubs, I’ve been asked multiple questions about playing time. Who gets the bulk of it? Is Jorge Soler now a part-time player? And wasn’t Javier Baez supposed to get some at-bats in the outfield?

I think people are missing the point.

First off, if you wondered these things after Fowler’s return, you should have been asking those questions even before Chris Coghlan was traded and Fowler re-signed. The Cubs had four starting-caliber outfielders then, and they have four now, but for some reason Coghlan never got the same level of respect as Soler.

I understand that Soler is a great physical specimen and everyone assumed he was to be the everyday right fielder this year, but I don’t think it was that cut and dry. Coghlan’s OPS, a pretty all-encompassing stat, was .784 last season while Soler produced a .723 mark. And Coghlan was easily a better defender, save for Soler’s arm. And once again Soler missed time due to injury and struggled when the temperature fell below about 45 degrees, which seemed to happen often both early and late in the season. But Soler had those nine plate appearances in the National League Division Series, which seemed to define his year. He got on base nine times in a row using a keen eye and/or some wicked contact, giving hope to his 2016 season.

View media item 1932557

In any case, manager Joe Maddon had a playing-time problem before Fowler’s return, and he supposedly has one now -- it’s just moved positions as Jason Heyward is back in right and Soler is mixing in with Kyle Schwarber in left. Schwarber is another player who still has work to do on his game. There’s no reason to believe he won’t improve, but remember he went just 8-for-56 against lefties last year, with a .213 on-base percentage, and had those miscues in the field he’d like to eliminate. Of course those numbers should go the right way with more experience, but the Cubs are in a win-now mode, so why not have backups like Soler or Baez around? They would be starters on other teams. That’s pretty cool.

But there is a bigger issue at play and it involves Maddon’s overall managing philosophy: Less is more. We’ve seen how that manifests itself in less batting practice and later arrivals for games, but it’s also true for overall playing time. With a stacked roster, Maddon can rotate guys in and out. He would do this anyway, but now he’ll match up players such as Schwarber, Baez, Ben Zobrist, Miguel Montero and even Fowler and Addison Russell to get the most out of them. Some of them will play most of the time, but Maddon won’t hesitate to exploit a good matchup while getting rest for a regular. If he wants he can use some of his players as mega-platoon guys. As much as Schwarber might want more playing time, just think what his numbers might be against righties only? Or Soler against lefties only? Fowler had some bad moments against certain pitchers last year, so Maddon can even bring him in and out of the lineup more if he wants. It’s why when asked if Fowler is his leadoff man Maddon answered, “When he’s in there.” The Cubs manager has a luxury few in the league possess: deep, deep talent.

With crazier travel schedules than ever, combined with rules against the use of drugs including amphetamines and steroids, Maddon’s style is perfectly suited to dealing with an abundance of starting players. He’ll use them all to keep his team fresh. His ways come from years of experience, starting as a coach in the Angels organization.

“It always seemed as though we ran out of gas,” Maddon explained. “I saw guys fade by the end of the season.”

His realization that players need more rest -- even stars in a pennant race -- has evolved over time. He once thought the old ways were the right ways.

“We hit a lot,” he said. “I was the hitting coach and I thought that was the right way to do things, too.”

View media item 1932556

He has changed his beliefs, and it coincides with the changes in the game. He foreshadowed how he might manage this season last year in the second half, when Schwarber came up, Montero returned from a thumb injury, Starlin Castro got hot, Soler returned from injury and then Baez was recalled and became a contributor. He mixed and matched and the offense took off. He exploited the matchups that best suited his hitters, while getting rest for old and young alike.

“I don’t care what birth certificates say,” Maddon said. “I’m living it [the grind] myself. I believe in keeping the mind sharp. If the mind is sharp, the body will follow.”

Maddon will go on and on about the value of rest, so in his mind the questions about playing time are moot. First off, players are going to get injured, so like a football team with a great backup quarterback, the Cubs have guys who are ready to go. By the time spring is over, Baez will be proficient at every position, save pitcher and catcher. He’ll slide right in as a starter in the infield if someone goes down. In the meantime he’ll be getting some starts and entering plenty of games later for defense, anyway. They may not miss a beat with Baez. We already know the team has an extra outfielder in Soler or Schwarber or Fowler or whomever. And if everyone is healthy, Maddon can use his matchup machine like he did late last season, while reducing the workload.

“There’s all these factors involved and then all this stress,” Maddon said. “Whether it’s self-inflicted or something from the outside. However you process stress that makes you fatigued also.”

Make no mistake, Maddon’s ideology is different than the norm. Keeping players guessing their roles -- and that includes relievers in the bullpen -- has always been frowned upon. But somehow Maddon has turned it into a positive. The use of an entire roster also creates a camaraderie you can’t fake. How often did the team go nuts last year when 25th man Jonathan Herrera, or players like him, had a big moment in a game?

Maddon wants his players ready at all times for all things. He believes that’s what keeps them sharp, instead of adhering to the same routine every day. So how will Maddon use everyone? He’ll just do it. And it will be a killer for the opposition.

“Most of the time with teams you have a lot of that depth at Triple-A, but we have a lot of that depth with us all year,” Maddon said.

So back to the manager’s original thought on all this. One he and Cubs management have expressed so simply since putting together a powerhouse team.

“It’s a good problem to have,” Maddon said with a smile.

Opening day 2014

Bonifacio

Lake

Castro

Rizzo

Olt

Castillo

Shierholtz

Barney

P

Opening day 2016

Fowler

Heyward

Bryant

Rizzo

Soler

Schwarber

Zobrist

Russell

Montero

CVO_RN95

formerly shoegamer19

- 1,998

- 549

- Joined

- Oct 15, 2014

I got tickets to 2nd home game of the season, I'm excited!

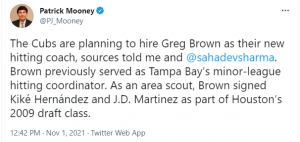

Chicago Cubs -- Grade: A+

Key acquisitions to date: Jason Heyward, John Lackey, Ben Zobrist, Dexter Fowler, Adam Warren, Rex Brothers, Trevor Cahill.

The Cubs have had a dominant offseason, highlighted by the signing of star outfielder Heyward, the best defensive right fielder in the game. Even before that signing, things were looking pretty rosy in Chicago. The Cubs made one of the best-valued free-agent signings of a starting pitcher when they landed Lackey on a two-year deal. They really improved themselves with the acquisition of Zobrist, who will give them better balance in the lineup, as well as improved defense at second base and the corner outfield positions and important leadership for their young players. Fowler fell back in their lap this week, agreeing to a one-year deal that will allow Heyward to remain in right field and gives the Cubs the solid lead-off hitter they had last year. Warren, who will also compete for a spot in the starting rotation, should help shore up the bullpen, and Brothers might end up being one of the best under-the-radar signings of the offseason. I predict that the Cubs will be the only team to win 100 regular-season games in 2016. It’s only a matter of time before Cubs president Theo Epstein becomes the highest-paid baseball executive in baseball history. He’s on his way to a Hall of Fame career.

- 1,888

- 504

- Joined

- Sep 7, 2011

i had a dream that Theo signed a lifetime deal.

- 37,287

- 19,666

- Joined

- Nov 17, 2004

i had a dream that Theo signed a lifetime deal.

omg me too!

- 1,888

- 504

- Joined

- Sep 7, 2011

omg me too!

I woke up off my couch this morning and turn straight to ESPN to see if it was really true.

Last edited:

- 1,888

- 504

- Joined

- Sep 7, 2011

Miguel Montero 5-5 with all 5 hits to LF to start the spring.

His bat is hot in the spring. I hope it carry over into the regular season.

- 1,888

- 504

- Joined

- Sep 7, 2011

Addison Russel showing some power and Jason Hammel pitched some good innings today.

- 44,001

- 16,368

- Joined

- Apr 23, 2014

Can someone post the 2016 MLB thread link? Please and Thanks

Perhaps the best part about the talent on this particular Cubs team is its unbridled youth.

Even after enormous breakout seasons from guys like Kyle Schwarber, Kris Bryant and even Kyle Hendricks, we get to look forward to potential breakouts from other guys like Jorge Soler, Javier Baez and Addison Russell*.

The latter, though, has been drawing an immense amount of praise from coaches, players and front office executives already this Spring.

After an impressive rookie season in the field, Russell looks ready to breakout on offense, as well. Or, should I say, continue his breakout from last season.

To be certain, Russell slashed a so-so .242/.307/.389 over 523 plate appearances in 2015 (although, he was actually the eight best qualified shortstop, via wRC+ and wOBA), but he got much better as the year went on. In the second half of the season, for example, Russell slashed .259/.318/.427 with a 101 wRC+ and just a 25.8% strikeout rate as a 21-year-old shortstop playing Gold Glove defense.

For the most part, the projection systems are remaining lukewarm on Russell, projecting modest increases in most statistics, but the FanGraphs fan projected system is expecting much bigger things: .263/.334/.430 with 16 HRs and 4.7 WAR. If he comes close to reaching those numbers, the Cubs will have quite the embarrassment of riches (and I don’t use that lightly).

But here’s the thing: he doesn’t have to come close to those numbers to be an extraordinarily valuable part of the team. Even with the relatively mediocre offense last season, Russell was a 3 win player in just 142 games. Given a full season of chances with more experience under his belt, Russell has an outside shot of being a 3.5-4 win player based on his defense alone. But if you can believe it, even that is apparently getting better.

Here’s what some players, coaches and executives around the Cubs had to say about the Cubs young shortstop this Spring (via Peter Gammons):

“It’s unbelievable what he’s becoming,” says David Ross.

“His first step quickness is as good as you’ll see,” says bench coach Dave Martinez.

“That first step, is so incredibly quick he has to be close to the best shortstop in the league defensively. And he’s going hit,” says GM Jed Hoyer.

Addison Russell is improving on defense, and there’s no reason to believe he couldn’t. At just 21 years old, he was like a vacuum at shortstop after spending the first half of the season learning second base on the fly. Once he made the switch back to short, though, it was clear that he could be truly elite in that role.

The metrics, although in samples small enough that you don’t want to draw too many conclusions just yet (especially with advanced defensive metrics), matched what the eye test was telling us about Russsell at shortstop.

His UZR/150 (20.4) in 2015 was second best in baseball, ahead of guys like Francisco Lindor and Andrelton Simmons, and his DRS (10) was tied for fourth most, despite splitting time between two positions (this is counting only the runs he saved at SS, which contained far fewer opportunities than his counterparts around the league). It’s difficult to imagine what a defensive breakout for a guy like Russell would look like, but I’m guessing Cubs pitchers are happy to have him.

Even Peter Gammons is picking up on the hype: “No place have I been this spring where any player has caused as much of a burn as Addison Russell …. Everyone around the team from the clubhouse to front office believes this is his breakout season. If, as his peers anticipate, Russell blossoms into a 20 home run guy, the Cubs will have one of the deepest lineups in the league.”

So, while you’re daydreaming at the office about the potential for players like Kris Bryant, Anthony Rizzo, Kyle Schwarber and Jason Heyward, remember: Addison Russell is firmly in their tier and has a chance to begin reaching that potential in just three weeks.

- 44,001

- 16,368

- Joined

- Apr 23, 2014

Can someone post the 2016 MLB thread link? Please and Thanks

Thanks

- 1,888

- 504

- Joined

- Sep 7, 2011

Whats the deal with Bumgardner thinking Heyward trying to still signs during an spring training game. i stop liking dude since he lied to me at Nats park. I told him to give me a ball during warms up. he said give him a minute. only a minute later he told me no. LMAO!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!! it was a 4th of july game Giants-Nationals. My brother a Giants fan.

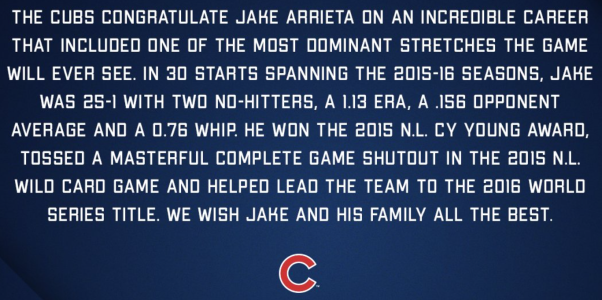

“I pitched for years not being comfortable with anything I was doing. I was trying to be somebody else.”

—Jake Arrieta

Battered and left for dead, Hugh Glass, as the legend goes, wriggled and stumbled with neither weapons nor supplies across 350 miles of feral upper Midwest frontier in 1823. That quintessential American legend of rugged individualism has been retold in print, in film and now, in spirit, on the like-bearded face of Cubs pitcher Jake Arrieta.

The beard is thoroughly 19th century—dark, as thick as ancient woods, unkempt and redolent of Arrieta’s most recent meal. From 60 feet, six inches away, especially at night, Arrieta gives a hitter the visage of Pestilence, the horseman of the Apocalypse: the expansive swath of black whiskers, the bushy brow scrunched into a knot, the flat brim of the cap pulled low, obsidian eyes cutting through a veil of gloom. It is a face that mimics Arrieta’s dark intention with the baseball: Give away nothing.

“Beast,” says his wife, Brittany. “That’s our nickname for him. I would not like to face him if I were a baseball player. You don’t know what’s going through his mind. You can’t even get the guy to flinch.

“Not everybody can pull off that beard. His back and chest and face are all hairy. We have a werewolf in the family. And it’s like his eyes are locked in on you.”

The real mayhem begins when Arrieta slowly bows his head, taps his right foot in the dirt in front of the rubber—a reminder that the impending violence comes from his entire body, from the ground up—and lifts his left leg. Here ... it ... comes. Hitting a baseball has almost never been more difficult than it was against Arrieta in 2015.

At 6'4" and 225 pounds, broad-shouldered and thick-chested, the 30-year-old Arrieta is one of the strongest pitchers in the game. “And those legs and glutes,” Cubs bullpen coach Mike Borzello says, “are unmatched in baseball.”

Arrieta must be this strong to throw a baseball the way he does, such is the torque he asks of his body. He pushes off the far third base side of the rubber, closes his front to the hitter, raises his left shoulder higher than his right and strides with his left foot toward the third base dugout. At that moment it appears as if Arrieta is trying to heave a ball into the second deck on the third base side of the stands. But suddenly, mid-flight, he appears to change his mind. No, throw it over here! His hips spin open—belt buckle facing the hitter—and then his torso spins. This separation between the two twisting actions, like one tornado atop another, is a key to power pitching. Only then, after the ball is “loaded” behind his head with his arm bent at less than 90 degrees, does the arm begin to fire. It’s as if Arrieta is throwing around a corner.

The flight of the baseball is menacing. It comes at the batter not only from an extreme angle but also at high speed (up to 98 mph) and almost always with ferocious spin that causes late movement right or left and down.

“The first thing that stands out is that he can throw the ball so hard and make it go both ways,” says Giants catcher Buster Posey, the only player to manage a hit off Arrieta with a runner in scoring position after Aug. 15. “You don’t see a guy who can two-seam the ball at 95 and throw a cutter at 93, 94. Usually it’s one or the other. And he’s got a power curveball to go with them.”

The cutter, Arrieta’s signature pitch, also resembles a slider. It’s a freak of physics that he throws anywhere between 83 and 95 mph on four different planes. Since Arrieta joined the Cubs in 2013 he has thrown 648 two-strike cutter/sliders without allowing a home run. “It’s a closer’s cutter,” Posey says, “except for eight or nine innings, not one.”

No one dominated hitters quite like Arrieta did in his 15 starts after the All‑Star break last year, when he posted a record-low 0.75 ERA in 15 starts. After mid-July more men ran for president of the U.S. than scored an earned run off Arrieta (nine). “No disrespect to major league hitters,” says Chicago reliever Clayton Richard, “but it was like you were at a high school game or a Little League game, and there’s that one guy who just dominates. You just know the hitters don’t have much of a chance. That’s what it looked like—not just once, but every fifth day.”

Says Arrieta, “I don’t want to sound like an [***] about it, but I don’t know if that second half will ever be broken. It’s hard to put into words. Being in the same sentence as Bob Gibson, that’s incredible.” Arrieta finished the season with a 1.77 ERA while holding hitters to a .185 batting average. Since the mound was lowered after Gibson’s 1.12 ERA in 1968, only Arrieta and Pedro Martinez of the 2000 Red Sox have managed an ERA and batting average against that low.

This kind of history brings us to the part where Arrieta, bearded or not, resembles Hugh Glass. Of the 45 pitchers to post a sub-2.00 ERA since the live ball era began in 1920, Arrieta is among the least likely, having carried the second-worst career ERA (4.64) into that historic season. The Cubs acquired him midway through 2013 only because the Orioles gave up his pitching career for dead: With a 5.46 ERA in a Baltimore uniform, he was the worst starting pitcher since the franchise began in Baltimore in 1954 (minimum 60 starts). So what Arrieta then did, covering the ground from record futility to an all‑time great season in less than three years, was the baseball equivalent of crawling 350 miles through the frontier after getting mauled by a bear. This pitcher who was so bad that he wanted to quit is now revenant and savior—the revenant who haunts Baltimore and the savior for Cubs fans, who yearn for their team’s first World Series title since 1908. Doubt him, as Baltimore did, at your own peril.

“The only thing that can stop him now is injury,” says Dodgers first baseman Adrian Gonzalez. “Hitters are in trouble facing this guy. He’s just like Kersh [Clayton Kershaw]. Hitters are not going to adjust. C’mon. His stuff and confidence are that good.”

****

“I’m thinking about not playing anymore after this season.”

—Jake Arrieta, 2013

Before he was Beast, before he had unstoppable stuff and confidence, Arrieta was so lost on a pitching mound that he shared with Brittany his recurring thoughts about quitting baseball. This was three seasons ago, after the Orioles demoted him to Triple A Norfolk just four appearances after making him their home opener starter. He languished there for two months, interrupted by one start with Baltimore in which he gave up 10 hits and five runs in fewer than five innings, swelling his ERA to an unsightly 7.23.

He was 27 years old. He looked at his newborn son, Cooper, and realized that he didn’t like what the misery of pitching was doing to him as a father and husband. He needed only a few more credits to complete his business marketing degree from TCU. He was good with people. He could go into business, maybe sales.

An hour or so later the competitor inside Arrieta sounded an alarm: How crazy an idea is that—that you would stop playing this game you love?

But then the next time Triple A hitters smacked his pitches around the yard, Arrieta sank into the abyss of doubt again. Flight or fight, fight or flight. The waves kept washing over him. “Norfolk in general was O.K.,” says Brittany, who has known Jake since elementary school, “but I’m O.K. if we never [go] back.”

Arrieta was cursed with a great arm. Cursed because he threw the ball with such natural power that everybody expected more from him. After a year at Weatherford (Texas) Junior College, he was pitching in the Texas Collegiate League when TCU coach Jim Schlossnagle showed up at one of his starts to scout a reliever who was to follow Arrieta. After the second inning, as Arrieta fired in the mid-90s, Schlossnagle dialed his assistant coach and said, “Forget the reliever. Who is this Arrieta guy?” Schlossnagle made Arrieta an offer right through the chain-link fence separating the field from the stands. “Listen, our best pitcher just left campus, and 130 innings went with him,” the coach said. “I need you to come to campus and be our Friday-night starter.”

Says Arrieta, “I tell everybody to this day that that’s the best opportunity I’ve been given my entire career. Somebody like that, to have the faith in me after seeing me pitch just once.... I never looked back from that moment.”

Arrieta went 23–7 in two years at TCU, was drafted by Baltimore in the fifth round in 2007 and was the talk of the Orioles spring training camp just two years later, along with fellow starters Chris Tillman and Brian Matusz. “I’ve been watching pitchers for a long time,” gushed then manager Dave Trembley, “and I would say those three guys are as good as I have seen at any one time coming up through somebody’s system.”

By 2011, Arrieta had earned a steady run in the Baltimore rotation. Midway through that season pitching coach Mark Connor quit for personal reasons. He was replaced by bullpen coach Rick Adair.

At the time, Arrieta pitched with his crossfire style from the first base side of the rubber and started his delivery with his hands at his belt. A month later he was pitching from the middle of the rubber and swinging his hands over his head. A few months later the Orioles forbade their pitchers to use the cutter for fear that it sapped fastball velocity.

By the next April, Arrieta still pitched from the middle of the rubber, but his hands were back at his belt. By May he was back on the first base side of the rubber. By September he had trimmed his windup to a modified stretch position. By the next year he was back to the middle of the rubber with a huge change: Adair took away his crossfire step in favor of a stride directly to the plate.

Over the two calendar years under Adair, Arrieta went 6–16 with a 6.30 ERA. “There were so many things in Baltimore not many people know about,” Arrieta says. “I had struggles with my pitching coach. A lot of guys did. Three or four guys—Tillman, Matusz, [Zach] Britton—were just really uncomfortable in their own skins at the time, trying to be the guys they weren’t. You can attest how difficult it is to try to reinvent your mechanics against the best competition in the world.

“I feel like I was playing a constant tug-of-war, trying to make the adjustments I was being told to make and knowing in the back of my mind that I can do things differently and be better. It was such a tremendous struggle for me because as a second and third-year player, you want to be coachable. I knew I got [to the majors] for a reason, and I was confused about why I was changing that now. You feel everybody has your best interests in mind, but you come to find out that’s not necessarily the case.”

Adair, who took a leave of absence in August 2013 and remains out of baseball, told MASNsports.com last October that “the biggest thing” that held Arrieta back in Baltimore was a bone spur in his elbow that was removed in August 2011.

“But that was 2011,” Arrieta says. “I was in Baltimore in 2012 and 2013.”

“Your feel is probably the last thing that comes [back],” says Adair now. “It takes time to regain it. I’m sure he wasn’t comfortable.” In any case he has only positive things to say about Arrieta and his success: “I would tell Buck [Showalter], ‘This guy’s got the best stuff I’ve ever seen.’ ... He’s the best in the game.”

On the morning of July 2, 2013, the Orioles were 2 1/2 games out of first place and in the second wild-card position. They were blessed with an abundance of young power arms that could stock the franchise’s staff for years, including Pedro Strop, 28; Arrieta, Wei-Yin Chen and Troy Patton, 27; Matusz, 26; Britton and Tillman, 25; Kevin Gausman, 22; Dylan Bundy and Eduardo Rodriguez, 20; Josh Hader, 19; and Hunter Harvey, 18. Today, because of injuries, trades and ineffectiveness, only Tillman and, to an extent, Gausman are established starters in Baltimore.

At the end of every season Cubs president Theo Epstein asks his 40 or so scouts and baseball operations people to submit a list of major and minor league players they believe will flourish with a change of scenery and to explain why. Clashes with managers ... problems at home ... an injury kept quiet ... a positional logjam ... anything that could be holding a player back. As the Change of Scenery survey results came in after the 2012 season, the one name that kept coming up was Jake Arrieta’s.

The Cubs’ intelligence was clear: Arrieta was healthy and had an excellent work ethic but was stymied in Baltimore. It was the curse of the great arm. During an Arrieta start in April 2012, for instance, White Sox first baseman Paul Konerko told Baltimore first baseman Chris Davis, “That’s the nastiest guy I’ve seen in the past five years.” Another time, on a trip to Toronto, Arrieta was working out in the Blue Jays’ weight room when he noticed on the wall a picture of 2003 Cy Young Award winner Roy Halladay, who just two years earlier, with a career ERA of 5.77 after 57 games, had gone all the way down to Class A ball to overhaul his mechanics. I can be that guy, Arrieta thought. He meant come back from the nearly dead.

By late June 2013, Cubs general manager Jed Hoyer was engaged in discussions with Orioles GM Dan Duquette, who needed a veteran starter as Baltimore chased Boston in the American League East. Duquette was interested in Scott Feldman, who was eligible for free agency after the season. The Cubs, flush with top position players, were desperate to add power arms. Hoyer asked for Arrieta. Duquette quickly agreed. But Hoyer wanted another power arm. He asked about Strop, a reliever with a 97‑mph sinker who, like Arrieta, had an ERA north of seven. Duquette needed another player from Chicago to make it work. He agreed to take Steve Clevenger, a backup catcher with Baltimore-area roots. It was done: The Orioles traded Arrieta and Strop, two pitchers with mid‑90s velocity and three years of team control, for three months of Feldman and a backup catcher.

On the night of July 2, 2013, Duquette called Arrieta in Norfolk. “We appreciate everything you’ve done in an Orioles uniform,” Duquette said. “We just think it’s appropriate to move on.”

“Thank you,” Arrieta responded. “I enjoyed my time in Baltimore.”

“I really did,” he says now. “I learned so much. It got me to this point.”

Soon he heard from Chris Bosio, the Cubs’ pitching coach, a former righthanded pitcher who lasted 11 years in the majors with a crossfire delivery. “Look, man, I’ve been through a lot,” Arrieta told Bosio. “All I want to do is come over there and be myself and be a winner.”

“Jake,” Bosio said, “we know what kind of stuff you have. We want you to be yourself.”

Arrieta went back to throwing crossfire, from the third base side of the rubber. Bosio made some tweaks. They worked on keeping Arrieta’s head in line with the plate, which reduced his tendency to overrotate and pull pitches to the glove side. They focused on a shorter stride and getting the ball to the arm side, which led to a more consistent release point, which led to better fastball command, which opened up the cutter/slider as the kill pitch. “I was able to not hold anything back or feel like I was judged,” Arrieta says. “People had lost faith in me in Baltimore, and rightfully so. I knew that was not the guy I was. I was letting it out as hard as I could in a controlled way. I was across my body. I felt strong. I felt explosive.”

“I remember, in 2013, I faced Matt Harvey, Jose Fernandez and most of the nastiest pitchers you could think of,” says Dodgers catcher A.J. Ellis. “The guy with the best stuff of all was Jake Arrieta.”

Arrieta pitched to a 3.66 ERA in nine starts with the Cubs in 2013 and lowered that to 2.53 in 25 starts in 2014. Then Beast showed up.

One day after the 2013 season Brittany and Jake were leaving a French bakery in their hometown of Austin when he noticed a Pilates studio next door. Arrieta has always been a workout omnivore, devouring any discipline that will make him better: yoga, Olympic weight training, visualization, sports psychology.... Pilates? Sounded interesting. Arrieta figured he would take one or two classes a week. He walked into the studio and signed up for a class with an instructor named Liza Edebor. “I pitch for the Cubs,” he told her.

“Oh, that’s great,” she said. “I never heard of you. Let’s see what we can do.”

In the first half of the 20th century German-born Joseph Pilates developed a series of controlled movements to improve strength and flexibility throughout the body. Many of the movements involve the use of pulley systems on a machine called a reformer. After Arrieta’s first session with Edebor he told her, “We need to train together. This is life-changing.”

He took sessions three times a week. He ordered a custom-built reformer for Wrigley Field and put it in the only space available, a cramped storage room that doubled as manager Joe Maddon’s media interview room. Last season Maddon conducted media briefings while Arrieta ground through his Pilates workout just a few feet away.

In the off‑season Arrieta turned his Austin garage into a Pilates studio. Edebor trained Brittany and Jake there for an hour and a half six days a week, starting at 6 or 6:30 a.m. “Jake went from a regular-sized athletic guy to just ripped,” Edebor says, “and the only thing we did was Pilates.”

“It’s an incredible experience,” Arrieta says. “Pilates has been around a long time but maybe was taboo in this sport. I think it’s only a matter of time before you see a reformer in every big league clubhouse.”

The Cubs finished remodeling their clubhouse facilities this off‑season, giving one of the game’s most cramped quarters the second-largest footprint in baseball, behind only the Yankees’ facilities in square footage. The new Wrigley digs include a room devoted to the latest in training devices. It is known as the Arrieta Room. More reformers are on the way.

“What I noticed from Pilates last year was that I have much better control of my body,” Arrieta says. “I repeat my delivery consistently. My balance is much improved. And the mental and physical toughness Pilates requires to complete movements the correct way have directly helped me on the mound.”

Arrieta stretches two hours every day. He does yoga. He meditates. He undergoes mobility training called Functional Range Conditioning, which stresses his joints to ward off injuries from sudden movements, such as reacting to a bunt. He starts every day with up to 24 ounces of water and 24 ounces of cold-pressed juices. He eats four to six eggs for breakfast and then has small meals throughout the day. Before starts he prefers marinated chicken, quinoa, roasted vegetables and other “foods that will lead to clarity of mind,” as he puts it. Steak and potatoes? “Never before competition,” he says. “There’s no way I’d put that food in my body. It will directly correlate with my performance.”

About two hours before every start Arrieta climbs on his reformer. He runs through a progression of movements designed to awaken and stress parts of his body for competition: obliques, lats, shoulders.... This goes on for about 20 minutes. When he is done, he pulls on his uniform and headphones. In Baltimore he would play heavy metal such as Pantera or Metallica to get his heart rate up. But now he plays mellow ambient music such as Fleet Foxes. He has learned that it’s better to calm the body and mind to conserve energy. When he steps on the mound, Beast will be there.

Since 2013, when Epstein and Hoyer were desperate for power arms, Chicago has added Arrieta (2013), Jon Lester (2015) and John Lackey (2016). Last year the Cubs won 97 games, and pitchers acquired from other organizations made 159 of the 162 starts; three by Dallas Beeler were the only exceptions. No move helped turn Chicago into a 2016 World Series favorite more than trading for one of the worst starting pitchers in Orioles history and getting the next Bob Gibson.

As for a Cubs championship this season, “the wives have talked about it more than the guys,” Brittany says. “Now that Wrigley is getting its beautiful renovation, I have heard there may be plans in place if we ever won the World Series that we would sleep there, because the city would be so hectic.”

“We feel it,” Jake says of the expectations. “We’re basically the same team we were last year with three elite players added [Lackey, rightfielder Jason Heyward and second baseman Ben Zobrist].” The curse of the great arm remains. People once wondered if Arrieta would ever get his act together on the mound; now they wonder if he can ever pitch again like he did last year.

“I charted Randy Johnson for four years in Seattle,” Bosio says. “He was the most dominant pitcher I’ve ever seen. What Jake Arrieta did last year I’ve never seen as a pitcher or coach. It’s something we may never see again. It was violence with command. I think he can sustain this level.”

Maddon has already spoken to Arrieta about removing him earlier from games this year to keep him fresh through October. Arrieta, who said he was gassed after winning the wild-card game in Pittsburgh, agrees with the plan. Some baseball observers are concerned about the violence in Arrieta’s delivery and his cutter/slider.

But Arrieta insists that his crossfire motion is natural—he has pictures of himself at 10 years old throwing that way—and that he does not torque his wrist or elbow to spin his cutter/slider. He simply moves his fastball grip off‑center, to the ball’s Eastern hemisphere, and concentrates on getting his middle finger “on the front of the baseball.”

Arrieta’s cutter has become dominant because of his increased command and use of the two-seam fastball, which breaks in the opposite direction. The two-seamer has become so good that Arrieta rarely uses his four-seamer, the staple of his youth, which has less movement. “I trust how much my ball moves,” says Arrieta, who cut his walk rate in half last year. “I can throw it at you or this far off the plate and have it end up on the black. That’s where I kind of went to the next level. I knew what all my pitches were doing. Even in ’14, I didn’t have that ability.”

Back in the dark days with Baltimore, on June 3, 2012, in St. Petersburg, Arrieta was so lost that after getting knocked out in the fifth inning by Tampa Bay, he sat in front of his locker and could not remember how it had happened. All he could remember was how much time he spent thinking about mechanics on the mound. Am I balanced? Is my front side where it needs to be? Is my landing spot good? He had to look at the video the next day to know how he gave up four runs. “And I was looking at somebody who wasn’t myself,” he says.

Now he doesn’t even like to use the word mechanics. He thinks about the way his body moves through space. He is playing the concert piano without sheet music. His feel for pitching is so heightened that he remembers three strikes against Chris Johnson in one at bat in Chicago in 2014 in a tactile way. “I remember the way the curveball spun off my index finger,” he says. “I could feel the force of the friction of that hard cutter at 93. I remember raising the bill of my hat—this is something Boz talked about a lot—to throw a four-seam up. And if you’re trying to go underneath the strike zone, tilt the bill of your cap down. If somebody had told me all that when I was 19, I would have said, ‘What the hell are you talking about?’”

Maddon, when asked what impresses him most about Arrieta, says, “His constancy of character. I don’t think I’ve ever seen anybody work like he does, and when he plays, there’s an extreme calmness about the guy. When I speak to him in the dugout during the game, I can have a conversation with him. A lot of guys you can’t. He looks you right in the eye, he speaks slowly, there’s never any heavy breathing. Among all the pitchers I’ve ever had, he is in the present tense as well and as much as anybody.”

When the legend of Arrieta is told years from now, it will always be about the journey from lost to found, the way it was for Halladay, Johnson, Sandy Koufax and the few other exceptions who crawled through baseball’s wood and dale to reach pitching greatness. For now, though, Arrieta is truly of the present. He has trained his body so well and so hard that with his eyes closed, he can execute his violent pitching motion and land square and balanced every time.

“We screw up. We’re human,” he says. “But what I think is, How close can I get to perfection? And if we try to be perfect, we can drive ourselves crazy, but we can be great. We can be close to perfect.”