- 7,384

- 10,175

- Joined

- Dec 29, 2012

Interesting read on how white rappers have found a way to succeed without necessarily being "accepted" pretty much sidestepping the larger part of hip hop world in the process.

http://www.nytimes.com/2016/08/21/arts/music/white-rappers-geazy-mike-stud.html?_r=0

Edit: I just fixed the formatting

http://www.nytimes.com/2016/08/21/arts/music/white-rappers-geazy-mike-stud.html?_r=0

Edit: I just fixed the formatting

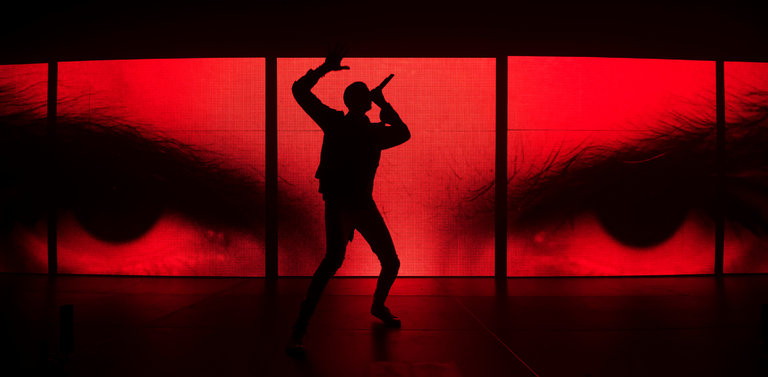

Last month, the white rapper G-Eazy — a handsome ectomorph sporting a motorcycle jacket and 1950s-slick hair — headlined a show at the Barclays Center in Brooklyn, part of a weekslong tour. Over the last couple of years, this Oakland, Calif., musician has evolved from regional curio to legitimate pop contender: He appears on the lead single from the forthcoming Britney Spears album, and in March, his song “Me, Myself & I” with the guest singer Bebe Rexha — from his platinum album, “When It’s Dark Out” — went to No. 7 on the Billboard Hot 100.

But G-Eazy has achieved a large chunk of this success via a hip-hop side door — not reliant on traditional gatekeepers like hip-hop radio or the support of an established black mentor. And his big single is like a simulacrum of a mainstream hip-hop hit. It has the same structure as a conventional hip-hop crossover attempt — rapper on the verses, singer on the hook — but here, both rapper and singer are white.

The most revealing aspect of the G-Eazy tour was its promotional image: a painted tableau of G-Eazy and his fellow headliner Logic (born to a black father and white mother), flanked on either side by the opening acts, YG and Yo Gotti, both of whom are black. But in a sleight of hue, everyone in the image appears to have similar skin tone. Race has practically been erased.

This gesture was avoidant, devious, disingenuous, rude. It was an inducement to overlook the show’s discomfiting racial dynamic, suggesting that the issues brought up by its lineup — with two popular black rappers, each with more radio and chart success than the headliners, relegated to the evening opening slots — have little to do with race.

That is, naturally, absurd, but it is a clear reflection of a somewhat unexpected emergent racial reality in hip-hop. White rappers — especially in the wake of the success of Macklemore & Ryan Lewis and, to a lesser degree, Iggy Azalea — are now finding paths to success that have little if anything to do with black acceptance.

For decades, white rappers who have reached wide renown — and plenty who never did — have employed a handful of familiar strategies. Initially, a co-sign — an imprimatur of authenticity, or at least tolerance, given by an established black artist — was essential. Think of Dr. Dre shepherding Eminem, or Run-D.M.C. taking the Beastie Boys on tour. (By contrast, remember the struggles of the nonsponsored Vanilla Ice.) More recently, fealty to the genre’s black-built history has been essential, as evinced by nostalgists like Action Bronson and Your Old Droog.

But now we have arrived in the post-accountability era of white rap, when white artists are flourishing almost wholly outside the established hip-hop industry, evading black gatekeepers and going directly to overwhelmingly white consumers, resulting in what can feel like a parallel world, aware of hip-hop’s center but studiously avoiding it.

This is striking, and it indicates a potential sea change. Hip-hop has long been a site of racial borrowing, but it has resisted whitewashing, owing to a combination of politics (explicit and implicit), its sustained connection to and dependence on the creativity of young black musicians and also its increasing financial viability (for some). It’s been inevitable, given how widespread the genre’s popularity and influence is four decades after its birth, that gobs of white rappers would come along, craved by white audiences. But until recently, the most visible white artists have generally operated with deference, understanding their role in the historical ecosystem.

This latest wave of white rappers, however, is demonstrating how many different ways there now are to try to elide racial conversation while still making rap music. It is an especially vexing moment for this, given how black pop, thanks to stars like Beyoncé and Kendrick Lamar, is increasingly political, and discussion of black cultural erasure is becoming commonplace on social media and beyond.

Take, for example, Mike Stud, a former all-American baseball player at Duke University who turned to rapping after an injury derailed his sports career. A few years ago, he was among a handful of white rappers working a frat-rap angle, and he is that mini-scene’s most prominent survivor. Nowadays he’s essentially a Drake clone, as heard on his recent single “Say No More,” and his latest album, “These Days,” which debuted atop the iTunes hip-hop chart in January. His signature catchphrase, a sort of elongated “yup,” is essentially lifted from the R&B singer Trey Songz.

Even if he isn’t innovative, he’s popular — enough to star in his own reality series, “This Is Mike Stud,” which just completed its first season on the Esquire Network. The show is an ode to binge drinking, coupled with a “Girls Gone Wild” approach to gender relations. In city after city, Mike Stud downs bottles of alcohol, signs body parts and raps. Over eight episodes, race is never once mentioned explicitly. The only time in the entire series when he looked genuinely uncomfortable was at a show in Orlando, Fla., part of a larger festival and not one of his own boisterous, inebriated crowds. “It’s a different lineup than we are used to,” his tour manager says, “and it’s not something that he particularly fits in to, but it’s something that was booked, and it’s a weird vibe, but it’s a show that we have to do.”

Perhaps it’s just a coincidence that apart from one member of the opening act Mike Stud has brought with him, no other act on the bill is white. In the clips of his performance, he’s subdued, seemingly reluctant to put the fullness of his act on display in this environment, as if it wouldn’t be smiled upon in this room or were a secret in need of protection.

Every other Mike Stud concert depicted on the show is crowded and flirts with bacchanal. This sort of touring success with white rappers — see G-Eazy — isn’t unusual. Many of them operate outside the major label system, but they have booking agents, which lets them build a touring base that they can in some cases ride all the way to arenas, bypassing hip-hop clubs, the usual proving ground.

Mike Stud’s understanding of the difference between his usual show and the Orlando outlier suggests at least a whiff of self-awareness about his unusual relationship to the rest of hip-hop. Self-awareness isn’t always an optimal commercial strategy, however — look at Macklemore & Ryan Lewis, who returned earlier this year with an album that took pains in places to pay homage to hip-hop’s black roots and current stars but was largely met with a commercial shrug.

Macklemore has always had an agonized relationship to white privilege, though — in a sense, his pop breakthrough was a breather between periods of righteous self-awareness. But not all white rappers are so burdened. For some, the freedom afforded them by their success verges on entitlement.

For Post Malone, an artist who toes the line between singing and rapping, and hip-hop and spooky electric folk, that has meant pushback on the very idea that he’s making rap music at all. His 2015 hit “White Iverson” was a hip-hop song in principle but not style — his is a genuinely postrap hybrid, building on the genre’s aesthetic and topical points and overlaying them with Bon Iver-like digital effects.

That ambiguity, in part, led to a dust-up over his absence this year from the cover of the hip-hop magazine XXL’s annual “Freshman Class” issue, a catalog of important rising rappers. After the magazine’s editor said that Post Malone’s representatives had told her he was trying to distance himself from hip-hop, he replied by saying that hip-hop was just one tool in his arsenal: “I want to continue making hip-hop. I want to continue writing songs on my guitar. I want to continue to work with talented artists across any genre,” he wrote on Instagram.

In the past, though, he’s been less diplomatic, telling an interviewer in 2015: “I’m not a rapper. I’m a artist. I don’t make rap music. I might rap, but I don’t make rap music.” In an earlier era, this would be blasphemy, but today the hemming and hawing is tacitly accepted.

An artist who did make XXL’s Freshman cover, and stirred up even more controversy as a result, is Lil Dicky, a comic-rapper who broke out last year with “Save Dat Money,” a song about how much of a skinflint he is. Unlike Macklemore & Ryan Lewis’s “Thrift Shop,” which was a repudiation of hip-hop excess (problematic in its own way), this was something different, as was clear in the video, in which Lil Dicky tries to score all the hallmarks of a traditional rap video — a mansion, a supercar, a yacht and so on — without paying for them. This is tricky, borderline-offensive stuff: He’s borrowing the excess the genre specializes in, trying it on, then making an argument against its worth while wearing it. That fine line extends to Fetty Wap and Rich Homie Quan, both black artists who also appear on the song and who are apparently forgiving of Lil Dicky’s contradictions.

In interviews and online, Lil Dicky defends his musical choices as satire, and they may well be. But his 2015 album “Professional Rapper” — the cover is his actual résumé — and his earlier work displays a lumpy jumble of entitlement and irony. In interviews, he’s spoken of the burden that choosing to rap has placed on his future job prospects, but doesn’t seem to have considered how such a choice might be experienced by someone without a résumé to place on an album cover.

Lil Dicky’s forever-arched eyebrow serves as a distancing mechanism, a tool to put him beyond reproach, regardless of the scale of his racial infractions. G-Eazy could use his pop success to do something similar (and more sincerely), but his narrative is more complicated than any of his peers. He was a minor player in the Bay Area hip-hop scene of the late 2000s and early 2010s, making a combination of contrived songs, like his updating of Dion’s “Runaround Sue,” and breezy pop-hyphy numbers like “Far Alone.”

Though his biggest success has come in collaborating with white artists — G-Eazy has become a go-to guest rapper for white singers, including Ms. Spears, Grace, Nathan Sykes and Marc E. Bassy — he’s still toggling between similar extremes.

That was clear at Barclays Center, where between his pop-oriented songs, he went out of his way to show hip-hop bonafides, and also to make it clear which legacy he saw himself belonging to. He brought out the black artists Jadakiss, Nef the Pharaoh, Ty Dolla Sign and Yo Gotti. And he invited YG back out during his set so they could perform the remix of YG’s anti-Donald J. Trump anthem, one with an emphatic, unprintable title.

“A Trump rally sounds like Hitler in Berlin,” G-Eazy rapped, deploying his white privilege as something more than a tool of career advancement.

Last edited: