- 37,287

- 19,666

- Joined

- Nov 17, 2004

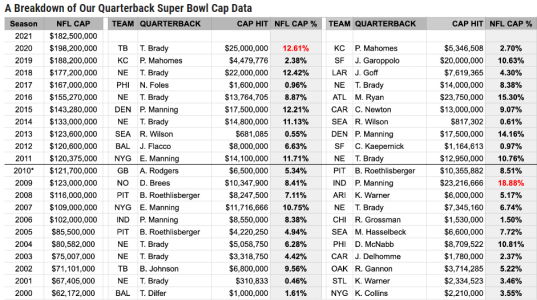

Seahawks have been smart in locking up their studs already. Hate them.

Do y'all think Dan Marino is better than Jeff George?

Do y'all think Dan Marino is better than Jeff George?

Last edited: