- 155,861

- 135,270

- Joined

- Oct 13, 2001

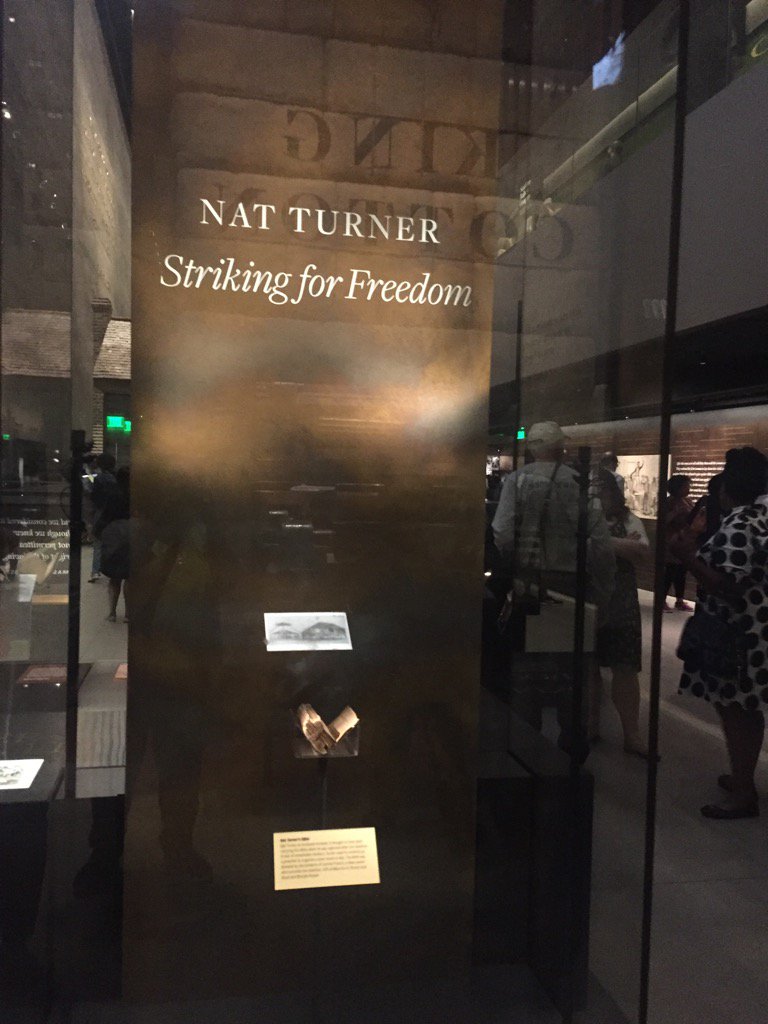

The daughter of a man born a slave opened the National Museum of African American History https://t.co/JnZy86R05i https://t.co/0RdYr0UHcp

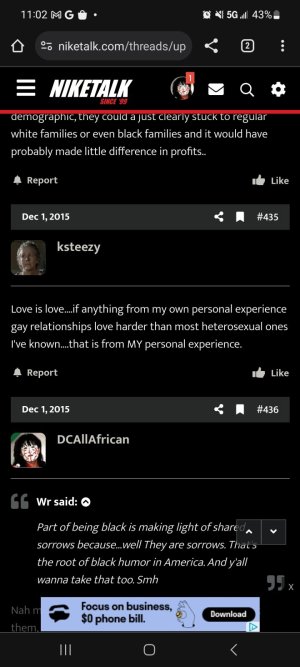

@ksteezy

Get over it right?

@ksteezy

Get over it right?