- 18,115

- 11,769

- Joined

- Jan 11, 2013

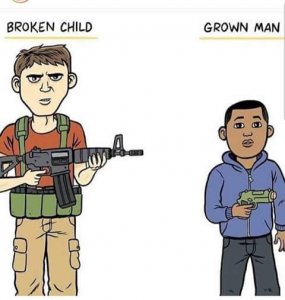

dude relax i was using your gif in response to the garbage @beacon ave south was talking

you didnt see where i quoted him?

anyway ill edit it so theres no confusion

you didnt see where i quoted him?

anyway ill edit it so theres no confusion